If he stays next year for his senior season, he'll end up being the mayor of San Francisco.

—Head coach Peter Barry, addressing the likelihood of junior guard Quintin Dailey entering the NBA draft

BALTIMORE, MARYLAND IN THE 1970s was a rough place.

Like so many other cities of the time, Baltimore was a victim of deindustrialization, beginning with the steel and shipbuilding factories closing down during the Sixties, creating a deep poverty that gripped the city and fostered an increase in crime and drug use. But that wasn’t all. State and municipal workers found themselves battling for better pay in the face of the Great Inflation that was fueled partially the United States abandoning the gold standard (and turning the dollar into a fiat currency), and partially by Keynesian economic policies1. Such policies proved feckless against “stagflation,” in which slow economic growth and high unemployment was buttressed by sharp price increases for consumer goods and services. On June 30, 1974, teachers, police, and other city employees went on strike in protest of a new municipal contract, scheduled to go into effect that year, that promised a paltry 20-cent raise, from $3.00 per hour to $3.20 (from $17.50 to $18.66, in 2022 dollars). Prison guards also walked off their jobs, leaving hundreds of inmates confined to their cells, their trials postponed, their rights to due process denied. In Southwest Baltimore, all twenty-two assigned beat officers abandoned their posts and soon the neighborhood was ablaze.

The strikes lasted two weeks, ending when the city leaders agreed to an immediate 25-cent raise with raises of 70 cents over the next two years. Corruption within City Hall came to light after a pair of FBI agents went undercover to, in the words of the Baltimore Sun, “root out suspected extortionate activities by city officials in charge of awarding contracts.” What the agents uncovered was a handful of enterprising demolition contractors who had been for many years rigging bids. The miscreants were sent to the slammer. The state’s attorney for Baltimore and a former congressman were also awarded proper accommodations behind bars.

In 1975, Baltimore was featured in a Harper Magazine article on the worst cities in America. But change was afoot. Mayor William Donald Schaefer, who was elected in 1971 and would serve in that role until becoming state governor in 1987, began to visualize the city as one of arts and culture, which would attract tourism, corporations, and higher-earning workers. An image makeover. Thus, he began a campaign to lure the film and television industries to Charm City. Movies such as Al Pacino’s …And Justice for All (featuring the famous line “You're out of order! You're out of order! The whole trial is out of order! They're out of order!”); Alan Alda’s The Seduction of Joe Tynan; a pair of John Waters flicks, Pink Flamingos and Female Trouble; and Blaxploitation thriller The Hitter were filmed in Baltimore. The sudden influx of money, as well as the exposure, was a huge windfall for the city.

IT WAS IN THIS ENVIRONMENT that a kid named Quintin Dailey rose to prominence. Born in B’more on January 22, 1961, the youngest of four boys, Quintin grew up in a neighborhood that featured intermittent bursts of violence. For his part, Dailey wanted no part of turf warfare; by the time he was a teenager, he was larger than most kids his age and, as a result, dished out pain on the football gridiron as a bruising tight end for the South Baltimore Police Boys Club. It was his brother, Anthony, who turned young Quintin on to basketball, as the two frequently dueled on the schoolyard with seven-foot-high baskets. “We played one-on-one to 100, by ones,” he recalled years later. “Anthony would let me get to 99, but I could never win. I’d go out there every day and practice. Then one day I threw in a hook with the score tied at 99, and [I] won. After that I started to enjoy the game.”

Dailey became a standout basketball player at Cardinal Gibbons School, an all-boys Catholic school that served grades seven through twelve. In three seasons, Dailey scored 2,844 points and led the Crusaders to back-to-back Baltimore Catholic League championships before graduating in June 1979. By all accounts, Dailey, who lost both parents while he was sixteen and was living with the parents of his girlfriend, Wanda Burton (her mother was Reggie Jackson’s older sister; Quintin and baseball’s “Mr. October” became close friends) was not only a phenomenal hooper, but a great student and a model citizen. “The worst thing that Quintin did during his three years on the varsity basketball team was to oversleep and be late for a team meeting during a Christmas tournament,” his coach, Ray Mullis, related years later. “As team captain, Quintin was very responsible and did an outstanding job. In fact, during a Christmas tournament his junior year, a couple of players decided to have a beer in their room. Before one beer was finished, Quintin was knocking on my door and saying, ‘Coach, we have a problem.’”

Two hundred colleges were hot on Dailey’s trail, but it was Dan Belluomini and USF who emerged as the leader and eventually snagged the talented 6-foot-4, 180-pound shooting guard.

Dailey would be one of a tripartite bumper crop of exciting young freshman to take the floor at War Memorial Gym as the 1970s dissolved into the ‘80s. Also arriving on the Hilltop that fall were versatile guard Raymond McCoy, from Chicago; and a 7-foot-2 center from nearby Novato named Rogue Harris who had missed his senior season of high school ball recovering from injuries sustained in a car accident. Also joining were John Hegwood, a sophomore guard-forward who had averaged 20 points and 10 rebounds per game in his one year at City College of San Francisco; and forward Mike Rice, a redshirt junior who, per NCAA rules, had to sit out a year after transferring from the University of Pittsburgh. Although the Dons were on sanctioned probation and barred from postseason play for the 1979-80 season, Belluomini was hopeful that this new group of kids would steer the Dons towards future NCAA Tournament berths.

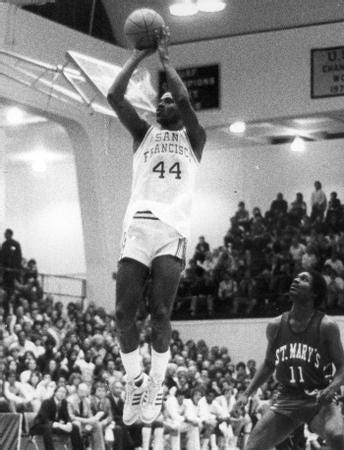

IF PROBATION WAS A BURDEN, the Dons didn’t feel its weight. They raced out to a 7-0 start to the season, before dropping their first game of the year against LaSalle Thompson and the Texas Longhorns in Austin, a game marred by late turnovers and a two-minute scoring drought. USF rebounded from that setback and would match their season-opening seven-game winning streak with a late-season seven-gamer. The Dons concluded the season with home victories against Portland and Seattle to finish 22-7 overall, 11-5 in conference. Their in-conference mark was good enough for the top spot in the West Coast Athletic Conference, two games over cross-Bay rival St. Mary’s. But due to the probation handed down by the NCAA on October 16, 1979, there would be no A.P. poll rankings and no tournament invite. Nonetheless, the 1979-80 season represented a harbinger of things to come, as Dailey paced the Dons with 13.6 points and 3.4 assists per game. Sophomore center Wallace Bryant, tasked with replacing the graduated Bill Cartwright, averaged 13.3 points and 10.4 rebounds per contest.

That would turn out to be Dan Belluomini’s final year, having resigned after the season at the behest of school president Reverend John Lo Schiavo in the aftermath of the Sam Perkins cheeseburger investigation. The next coach would be tasked with running a clean program.

Meet the New Boss

“He’s a quiet leader. Most coaches have the cavalry-general image, the dictator. I’m like that, but others, like Dean Smith, are more congenial. Pete’s like that, but he’s an honest, open guy who won’t try to manipulate people. Players will respond to that. I think he’ll do a great job.” If anyone could attest to new USF basketball head coach Peter Barry’s character, it was Neil McCarthy, Barry’s boss for three years as the head man at Weber State. The feeling was mutual. “Neil is an outstanding coach and I learned a lot from him.” Barry also knew Dan Belluomini, the two having crossed paths when Barry returned to USF for graduate school in the late 1970s. Barry had also coached high school basketball, and though he had played the sport, he wasn’t particularly great at it – by his own admission, he “had the touch of a mule” – and after playing on the Dons’ freshman team, Pete hung up the sneakers to concentrate solely on baseball. Dante Benedetti, the USF baseball coach, recalled that Barry “didn’t have a lot of talent, but he made himself a ballplayer through hard work and determination.” Barry was good enough to sign on with the Los Angeles Dodgers organization, playing two seasons of Single-A ball in Medford, Oregon, hitting .285 with virtually no power and no true defensive position. The Dodgers released him in 1971, and Barry returned to California, replacing McCarthy as head freshman coach at St. Patrick’s High School in Vallejo, California, before reuniting with him at Weber State. But after three years in the snowy climes of Ogden, Utah, Barry was ready for a change. Peter returned to USF for graduate school, met Belluomini, who had just replaced Bob Gaillard as head coach, and was offered an assistant’s role.

Now, suddenly, he was replacing Belluomini.

Barry knew the assignment: to continue the Dons’ winning tradition, but to do so within rules. No more recruiting violations. No more free Warriors tickets, no more use of staff phones, and, for God’s sake, no more unauthorized cheeseburger dinners. “We’re going to have a successful program,” the new coach said. “But it’s going to be an honest program right down the line. We just have to limit our recruiting to kids who are interested in USF and who can cut it academically. They’re out there. We may just have to work a little harder to find them.”

Peter Barry’s first order of business was to deal with the hemorrhaging of talent. Since the mid-1970s, the Dons recruited a little too well, stuffing the roster with high-upside players but were unable to find significant playing time for everyone. It finally caught up to them in 1980, as five players – McCoy, Rice, Guy Williams, Marvin DeLoatch, and Dave Cornelious – departed for other schools and the promises of greater opportunities.

The Dons’ key players from 1979-80 were returning, though. Dailey was entering his sophomore year, and he would be surrounded by experienced upperclassmen in Hegwood, Bryant, Ken McAlister, and Bart Bowers. And with the one-year probation having expired, USF could aspire once again to reaching the NCAA Tournament.

The 1980-81 season was a breakthrough for Dailey, who averaged 22.4 points per game, once again leading the team. He was rapidly emerging as one of the best players in the nation, but hardly anyone outside the Bay Area noticed. USF was disallowed from playing any nationally televised games during the probation year of 1979-80 and wouldn’t appear in one until the 1981 NCAA Tournament. The Dons finished the season 24-7/11-3, once again winning the WCAC, and finally receiving that coveted tourney invite with the new group. But the Dons were one-and-done, dropping a 64-60 decision to Kansas State University, a game in which the Hilltoppers held a ten-point lead with ten minutes to play. Dailey paced the Dons with 20 points, and 7-foot center Wallace Bryant dropped in 15. But USF fell languid in the game’s terminal minutes, struggling to score points while also playing passive defense, and KSU out-hustled them on every loose ball. “We lost our intensity,” Hegwood said afterward. “They just took the game away from us.” The Wildcats adjusted their offense in the second half, rotating two wing players while creating space for muscular 6-foot-8 forward Randy Reed to get whatever he wanted in the paint. “We kept moving, and we got good shots,” said KSU guard (and future NBA All-Star) Rolando Blackman.

Despite his outstanding performance throughout the season, Quintin Dailey still received no plaudits. “When the seemingly endless All-America teams were announced,” Roger Jackson of Sports Illustrated wrote in December 1981, “Dailey didn't appear on any of them.”

“The Chemistry is Right”

ENTERING THEIR SECOND YEAR POST-PROBATION, the USF Dons looked to repeat as conference champions and make a deep run in the NCAA Tournament. They had a shiny new toy in 6-foot-8 forward John Martens, a highly touted freshman out of Newbury Park High School in Thousand Oaks, California, who would be replacing the graduated Bart Bowers. They had their core four – Quintin Dailey (junior), Ken McAlister (senior, captain), John Hegwood (senior), and Wallace Bryant (senior) – all returning. Their bench would feature more depth than the previous year; should the Dons build a big enough lead, then Barry could count on the likes of Eric Booker and Eric Slaymaker and Crosetti Speight to run the second unit and give the main guys breathers. If all went well, another 20-plus-win season would be assured, perhaps coupled an 11- or 12-win total against the WCAC and a conference title, and, just maybe, a run to the Elite Eight (at least!) for the first time since 1974. For the likes of Dailey and Bryant, who had aspirations of playing pro hoops, the 1981-82 season would be a chance to pad their résumés.

The Dons would open the season with a nationally televised game against the Georgia Bulldogs of the Southeastern Conference. Beginning the season ranked No. 16, Georgia boasted the “Human Highlight Film,” 6-foot-8 Dominique Wilkins, who averaged nearly 24 points per game as a sophomore the previous year. But, first, the Dons had scheduled an exhibition tilt with the University of Victoria, British Columbia, a team that USF figured to overwhelm; a team the San Francisco Chronicle uncharitably characterized as “small, slow, and rooted to the floor.”

A team that nearly pulled the upset.

The final score – an 82-69 Dons triumph – doesn’t tell the whole story. USF turned the ball over 13 times, and often played out over their skis, trying to trigger a fast break when there was no fast break to be triggered. It was a close game until the final five minutes, when the Vikings ran out of gas and the Dons took control. Perhaps the Dons shouldn’t have taken them too lightly; after all, the Victoria Vikings had won the Canadian U Sports championship the previous two seasons, would win it again in for the 1981-82 season, then capture two more before the Eighties ran out. It was a strong program.

Nonetheless, with that tune-up in the rear view, it was time for USF to begin their latest march to the tournament.

WAR MEMORIAL GYM WAS PACKED. A total of 6,500 fans streamed their way through the building’s entrances, taking over both levels and spilling onto the floor behind the baskets. CBS was on hand to beam the game to all corners of the country, with veteran sportscaster Frank Glieber and former Michigan star Steve Grote behind the mikes. Baseball star Reggie Jackson, on hand to support Quintin Dailey, was also in the stands.

Georgia won the tip and clanked their first shot; a Dons rebound and fast break sparked a Bryant one-handed dunk to give the Hilltoppers the initial lead, sending the USF partisans into an early pom-pom-waving frenzy. “What a way to start the season!” Glieber enthused.

What a way, indeed. Making use of a fast-break and transition game that often left the Bulldogs looking like newborn puppies in quicksand, the Dons won 92-84.

It wasn’t easy. At one point late in the game, the Dons were behind, and Bryant had picked up his fourth foul. Pete Barry removed Bryant and John Martens from the game, subbing in guards Eric Slaymaker and Eric Booker, forcing both Dailey and senior captain Ken McAlister to play forward and present essentially a four-guard look capable of scoring points although giving up size. But the Dons did a magnificent job keeping Wilkins away from the hoop, where he was capable of damage, and limiting him to outside shots, where he was less lethal. “We were going to give him the fifteen- [and] twenty-footers,” said McAlister, who finished with 19 points. “We knew he was going to get his points.”

The Dons trailed just 42-40 at halftime, and Dailey had struggled, bonking nine of his 15 shot attempts. “Q told me in the locker room that he had to start working,” Hegwood said. “He was disappointed, but I told him to keep his head in the game and keep working.”

“After the first half, I made up my mind,” Dailey said. “I got mad. I started getting easier shots in the second half.”

Georgia went on an 8-0 run early in the second half, inflating their lead to 52-46. And that’s when both McAlister and Dailey took over, with McAlister providing the defense against Wilkins, and Dailey doing everything possible on the offensive end – passing, cutting, scoring. Dailey saved an errant Booker pass and drew a foul, sinking one free throw to increase the lead to five. Later, Dailey stole a Georgia pass and sent it to Booker, who hit a bucket to give the Dons an 82-74 lead with 2:39 remaining in the game. Then, with under a minute remaining and USF clinging to an 86-82 lead, Dailey drew a foul on Terry Fair and sunk a pair of free throws to ice the game.

“Every good team has a player who, if he takes control, they will win the game,” Dailey said afterward. “I had a feeling [in the second half] so I took over. One day it might be Wallace, one day it might be John. We have three players like that.”

As Barry told the media after their exhibition victory over Victoria, “The chemistry is right.”

Back in the Rankings, Back to the Tourney

USF BEGAN THE 1981-82 SEASON winning its first seven contests, beginning with the win over the Georgia Bulldogs, followed by a victory over the cross-Bay California Golden Bears, then taking down Rice, Iona, New Orleans, Colgate, and Bradley. Along the way, the Dons achieved something that hadn’t happened since early March 1979: an Associated Press ranking. By late December 1981, USF had broken into the A.P.’s top-10, settling in at No. 6.

A rematch with the Rice Owls, on December 28, 1981, during the semifinals of the Rainbow Classic in Honolulu, Hawaii, brought the Dons their first loss. USF got back on track the following night, besting an excellent Wichita State squad2, 84-74, to win the third-place consolation game.

The Hilltoppers got off to an inauspicious start in conference play, as the 11-1 Dons fell to a Pepperdine team that began the day with a 4-6 record. As the season progressed, Coach Jim Harrick’s Waves would reveal themselves to be damn good in their own right, sweeping through the WCAC and finishing with a 14-0 conference record. The Dons would lose three more times the rest of the year, falling to Notre Dame in a non-conference tilt on February 2, 1982, then losing by two at Santa Clara four days later, then dropping a rematch with the Waves at the end of the month. The Dons’ final WCAC record of 11-3 was good enough only for second place, thanks to Pepperdine’s undefeated romp, and USF’s return residency on the A.P. polls would be short-lived, as they slid from No. 6 in late December down to No. 11 by mid-January, then dropping to as low as No. 17 after the back-to-back losses to the Fighting Irish and the Broncos. Despite a 6-1 finishing kick, the Dons fell out of the Top 25 and would end their season without the coveted little number next to the school name.

It was still a very good season for the USF Dons, and as Dailey had affirmed earlier on, they had multiple players capable of emerging as the hero in any given game. There was the 104-78 blowout of Loyola Marymount, coming just two days after the first Pepperdine loss, in which Bryant pulled down 13 rebounds with a team-high 25 points in just 28 minutes of action. Wrote John Crumpacker in the San Francisco Examiner, the “unstoppable” Bryant had his way with Loyola’s Leonard Agee, and “could have had 40 points” had he played the entire game. Five days later, the Dons celebrated Dailey’s twenty-first birthday by crushing Gonzaga, 80-65, in front of 4,452 patrons at War Memorial Gym. Quintin posted 18 points, but it was the struggling freshman forward John Martens who had his best game of his young college career, knocking down nine of 10 free throws after entering the game having clanked 19 of his past 26 attempts. The next night, the Dons hosted the Portland Pilots and needed two free throws from reserve guard Eric Slaymaker and a last-second banker by gimpy forward John Hegwood (he had sprained an ankle during the Pepperdine loss) to eke out the victory. Dailey led with 28 points, and Bryant, who had a season-high 18 rebounds, threw down a thunderous dunk with a little over two minutes remaining in the game to give the Dons a six-point lead. But the Pilots refused to go away, and they would cut the lead to just one point with 1:06 remaining. That set up Slaymaker’s and Hegwood’s last-second heroics.

For the most part, though, the Hilltoppers’ statistics leaders on a game-by-game basis were Dailey (who led or co-led the Dons in points in 25 of the team’s 31 games) and Bryant (who led or co-led the Dons in rebounds in 22 of 31 games). A handful of times, Hegwood would show up as a leader or co-leader in either points or rebounds, and McAlister made an occasional cameo appearance. But make no mistake, the mitochondrial center of the 1981-82 USF Dons consisted of the 6-4 junior guard from Baltimore and the seven-foot senior center from Gary, Indiana.

DESPITE FINISHING THE SEASON OUT of the A.P. poll, the Dons’ final 25-5/11-3 record earned them an NCAA Tournament invite as the No. 9 seed in the Midwest region. Their first opponent, Boston College, was just a couple years removed from a point-shaving scandal that shook up the college basketball world and resulted in one player going to jail. The program survived the episode well, and the 1981-82 edition of the Eagles was a tough squad whose roster featured five future professionals, including their leading scorer, John Bagley (the 1980-81 Big East Player of the Year and future Boston Celtic), and reserve freshmen guard Michael Adams, who would become a starter as a sophomore and go on to play eleven seasons in the NBA, making the 1992 All-Star team. The Dons would have their work cut out for them.

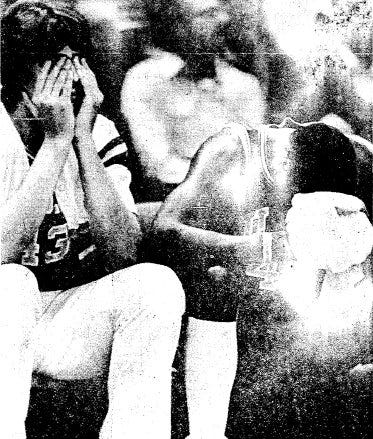

Then USF had to go and make things unnecessarily difficult for themselves, and the end result was a frustrating first-round tourney loss for the second straight year.

It took nearly three minutes for USF to get on the scoreboard, and for the rest of the first half their offense looked discombobulated. The Dons tried to force the action and wound up turning the ball over far too often. A frustrated Peter Barry had to call a timeout two minutes into the game to settle his troops down. “This game was lost in the first ten minutes,” the coach mused afterwards. “We acted terribly nervous. We rushed everything. It looked like we were playing with a five-second shot clock. Boston College didn’t force us, we forced our own tempo.

“I can’t remember ever doing that [before],” Barry said of the early timeout. “This is a senior-oriented team. But it was not going to happen. We could not get back on top.”

In truth, the Dons were never on top. The Eagles scored the first bucket of the game sixteen seconds after the tip and never trailed.

USF did make a furious late run to get back into the game, fueled by Dailey’s 20 second-half points, including 16 of the Dons’ final 20. “We were going 85 miles per hour in a 25-mile-per-hour zone,” Quintin said of the team’s first-half performance. “We weren’t even looking for each other. Two passes and boom – the ball is up.”

In addition, “I wasn’t getting the ball where I could operate. And then when I did get the ball, they hit me when I was in the wrong places.”

In the second half, Barry re-positioned Dailey to operate at the top of the key, and that triggered the star guard’s late scoring barrage. Three times in a two-minute stretch, Dailey hammered home big shots, with the third one cutting the B.C. lead to just one point with a minute-and-a-half remaining. The play that “broke our backs,” according to Ken McAlister, was when B.C.’s Martin Clark rebounded a missed free-throw from teammate Rich Shrigley, forcing USF to foul again in an attempt to get the ball back with time still left on the clock. The Eagles hit four more free throws to ice the game and give them the 70-66 victory. On their bench, the Dons were disconsolate. Once again, their season had ended prematurely.

Things around the basketball program were about to become much worse than early tournament exits.

Much, much worse.

The Downfall

VICTORIA BRICK WAS A TWENTY-ONE-YEAR-OLD nursing student at USF. A platinum-haired senior who stood 5-foot-4 and weighted 130 pounds, Victoria was about to conclude her studies and enter into the career field she had dreamed of entering since she was a child. As a graduating senior, she was also tasked with serving as the resident advisor (R.A.) on the third floor at James Phelan Hall3, a student dormitory just south of War Memorial Gymnasium that also housed a number of the school’s student-athletes. In her role as her floor’s R.A., Victoria was responsible for overseeing dorm life for other students: welcoming and looking after homesick freshmen, planning student events, enforcing campus rules, or simply being a compassionate and attentive ear for anyone dealing with the stresses and rigors of a university existence.

And, on occasion, questioning the motives of a couple of the school’s most visible athletes when they’re doing something curious, like, oh, shuttling bulky pieces of furniture from one floor to another.

At around one o’clock on the morning of December 21, 1981, Victoria Brick heard a noise outside her room. What the hell? It’s now Monday morning! Annoyed, but not wanting to shirk her duty, she opened her door and squinted out into the cramped, narrow hall. There, she saw two large men carrying a large mattress toward the elevator and recognized them as two USF basketball players, Eric Booker and Quintin Dailey. She knew both Booker and Dailey, and they were no threat. The duo were less than 48 hours removed from the team’s latest game, an 88-81 victory on Saturday over the Iona Gaels of the Metro Atlantic Athletic Conference, to seal the championship of the Golden Gate Invitational. Dailey, at the time the nation’s fifth-leading scorer, had tormented the Dons’ Big Apple visitors, dropping in 24 first-half points en route to 34 overall (along with four rebounds, five assists, and three steals). Booker contributed some late free throws to help seal the Dons’ victory. Quintin was voted the tournament’s most valuable player and was included on the all-tournament team alongside teammate John Hegwood and Rice guard (and future NBA All-Star) Ricky Pierce.

And now here were both Dailey and Booker, shuttling a mattress along the dormitory floor as the R.A. bemusedly looked on.

Victoria asked them what the were doing. Dailey replied that he was moving his mattress down to the second floor for the upcoming Christmas break. Just make sure you return it, she told him.

“Cool,” Quintin responded, as he and Booker entered the elevator.

Satisfied with the response, Victoria closed her door. She did not lock it.

VICTORIA BRICK FINALLY FELL ASLEEP around 3:00 a.m. Forty-five minutes later, she awakened, startled to see Quintin Dailey towering over her. “Quintin, what are you doing in my room?” she asked4.

“Your door was open,” he said.

“It’s awfully late.”

Undaunted, Dailey sat on Victoria’s bed, about six inches away from her. Victoria recalled that Dailey told her that he’d “had his eyes on [her] for a long time.” She smelled alcohol on his breath. He had been partying down on the second floor with Booker and Ken McAlister ever since taking the mattress down there. Feeling threatened, and not knowing if he was looking to assault her, Victoria tried to distract Quintin, engaging him in small talk and trying to convince him that they could hash out whatever feelings he had “at a later date.” It was almost 4:00 a.m. now, and she wanted nothing more than to go to sleep. She had classes in a few hours.

Dailey, inebriated and possibly feeling emboldened, asked Brick to kiss him. She refused.

“Why?”

“I feel in the condition you are in right now,” she explained, “it might lead to something else.”

“Well,” he said, “it just will be a little kiss.”

She still refused. “I will leave if you kiss me,” Dailey responded.

Promise? “Yes, I promise.”

She lifted her head up and kissed him. It just will be a little kiss.

No. This encouraged a drunken Dailey still further. He wanted another. Victoria refused. Angered, Dailey pushed Victoria’s shoulders down and demanded she kiss him again. Terrified, heart racing about 200 miles per hour, uncertain what this large, athletic man who’d consumed a few too many (probably for the first time in his young life) was about to do to her, she tried to distract him again. Talk some sense into him. She was a nurse-to-be, after all, and empathy was one of her strongest attributes. They talked about the Dons’ recent exploits – they were 4-0, and newly crowned champions of the Golden Gate Invitational Tournament – then she tried to steer the conversation to his girlfriend back home. The latter topic enraged Quintin - he didn’t want to talk about the girlfriend. “She is gone [and] she is not coming back,” he told her. “Well,” Victoria said, “I don’t want you taking your anger out on me.”

This riled Dailey even more. He pushed her head back and kissed her. When Victoria asked him again to leave, he reacted by pulling her bedsheets down.

He is going to rape me! she thought.

She sat up violently in her bed in an attempt to startle him, and then screamed for help. It didn’t work; he overpowered her and pushed her back down.

Shut up! He covered her mouth. Victoria later testified that that Dailey threatened to “pull a [gun] out and hurt me.” She also attested that she neither saw nor felt a gun on him.

Dailey said he had no plans to rape Victoria. But he also had no plans to leave her alone. “I want you to want me,” she recalled him telling her; he wanted her “to submit to him.”

Then, Quintin tried to pull Victoria’s legs apart; acting quickly, she twisted the bottom of the medical scrub gown she was wearing between her legs. He kept demanding that she kiss him, and she kept refusing. Dailey grew more agitated. He tried to pull the gown down as he kissed her on the neck with enough force to leave a mark. Victoria tried to reach for the phone on her nightstand, which triggered Dailey’s worst impulse yet: he put his hands on her throat and pushed her back down, clutching her in a chokehold.

Scared that she was about to lose consciousness, Victoria pulled a literal last-gasp maneuver. “I felt that if I acted like I was going to pass out sooner than I really would, he would get scared,” she later testified. She began gagging, which shook Dailey from his enraged fugue state. “I don’t want to kill you,” he said under his breath, then warned her to not say anything to anybody, “because it would ruin his reputation on the team,” she recalled him saying. Quintin tried once more to pry Victoria’s legs apart, but, dealing with both intoxication and now fatigue, he weakened and fell asleep.

Fifteen minutes later, she tried to wriggle away; having awakened him, the torture started all over again.

Dailey reacted by pushing her back down and “forcibly” kissing her. He then pulled down his pants and demanded Victoria fondle his genitals. She kept refusing; he kept insisting. Finally, Victoria did the only thing that she felt would save her from any more abuse. She grabbed his penis and masturbated him. “Number one, it would pacify him and he wouldn’t be so aggressive with me,” she later testified. “[A]nd number two, if he was able to ejaculate, he would not be able to rape me.”

She guessed correctly. Dailey eventually fell asleep again, this time a much deeper slumber. It was somewhere between 5:30 and 6:00 in the morning, and still pitch-dark outside. Victoria managed to slide out of her bed and flee the room. Dailey was later chased out of the building by another R.A., Charlie Reynes. Reynes testified that he had “chased [Dailey] down a fire escape. Then he started to swing something. It might have been a belt, I couldn’t see. I kept up the pursuit. I just wanted to get a look at him. I thought he was some Black guy out of the ghetto by USF. He was very fast. I went down Clayton Street [south of campus] for a block, then he turned left and went into a space between two buildings.” Reynes, who also testified to having 20/100 vision, admitted that he didn’t have his glasses on and had some difficulty seeing, making a positive identification impossible. He described the man he was pursuing as “6’2”, dark jacket, green pants. Dark complected, slender, strong.”

Victoria later told the dorm’s resident director, Ed Confino, about the assault, though she initially didn’t mention Dailey by name. Confino, who wasn’t a student but a USF employee, and having just taken the reins at Phelan Hall in October, suddenly had his first major problem on his hands. He suggested Victoria visit Dr. Sue Shoff at the counseling center. Confino accompanied her there. In the presence of both Shoff and Confino, Victoria revealed that USF basketball player Quintin Dailey was her assailant.

THE ATTACK HAPPENED IN DECEMBER 1981, in the midst of basketball season. Quintin Dailey was arrested in February 1982 and charged with five felonies. He plead guilty on June 4 to one count of aggravated assault and was sentenced to three months’ probation5. Later that month, the Chicago Bulls selected him in the first round of the NBA draft, seventh pick overall (they would take Wallace Bryant in the next round). Displaying no remorse, Dailey told the Chicago Tribune that he plead guilty to “keep my career going.” As a first-time offender of any type, Dailey probably figured on a light punishment; a not-guilty plea would tie him up with court dates and potentially affect his draft standing.

On June 25, 1982, four days before Dailey was drafted, the probation report was made public and university lawyers began an investigation. The report, which detailed Dailey’s attack on Victoria Brick six months earlier, also contained another Dailey admission: he had accepted thousands of dollars of sinecure pay from a USF booster named J. Luis Zabala.

THE ZABALA NAME WAS WELL known throughout the halls of the Hilltop. The family’s roots in northern California run as deep as the late eighteenth century, when a group of settlers arrived from Bilbao, Spain in 1794, and Zabalas have populated both the donor rolls and attendance sheets at USF. Albert J. Zabala (b. 1876; d. 1965)6 was perhaps the largest donor in the school’s history, having given over two million dollars through a trust fund. One of his sons, Honore, was a star soccer player for the Dons who later perished while fighting in World War II. Another, Reverend Albert Zabala, became a professor of theology at the school.

Luis, the youngest7, played high school basketball at St. Ignatius High School, where one of his teammates was none other than John Lo Schiavo, now the USF president. He graduated from USF in 1949 with a business degree, and after years of working in sales, he purchased a company, Electric Supply, in Salinas, California, a small town of about 30,000 approximately 110 miles south of San Francisco. He later expanded his business into both central and northern California and became a rich man in the process. His wealth and prestige and family connections to the school enabled him to become president of the Century Club, the USF booster club. As a child, Luis Zabala had dreamed of being a star basketball player at USF. As a moneyed middle-aged benefactor, he wanted nothing more than help the team out any way he could, because, as he later put it, “this is a streetcar university, and it seemed to me it needed something to rally around. I never felt we have to be No. 1 – just competitive.”

So, when the investigation into Quintin Dailey revealed that Luis Zabala had paid the star hooper stacks of cash for a no-show summertime job, it represented yet another domino to topple towards the end for the USF basketball program. And yet, this was only the most visible example of malfeasance. A Sports Illustrated report revealed that Peter Barry gave Dailey $200 to pay a car rental bill, a charge the coach denied. Another USF booster, Al Cleary, the president of a construction firm, paid the tuition of St. Ignatius basketball star Paul Fortier, a center-forward who was being recruited to the Hilltop.

For his part, Fortier knew nothing of the gift – his parents received the payouts – and he wound up at the University of Washington, with whom he would earn All-Pac-10 honors in 1986.

THE PROVERBIAL SHIT HAD HIT the fan. It was one thing to allow recruits to use athletic department phones or dole out Warriors tickets or, for crying out loud, to buy a high-school kid a burger; those were minor offenses that submerged the USF men’s basketball program into the tepid waters of short-term probation. The twin revelations that a star player — who was on the verge of going professional — had assaulted a coed in her dorm room and, oh by the way, was also receiving illegal cash sums from a member of a prominent booster family, were an atomic bomb that threatened to shut the whole operation down, possibly for a few years, possibly for a decade, possibly forever. Especially if the NCAA got involved. Perhaps some additional dirty laundry would come tumbling out. The basketball team could follow the football team into the realm of permanent extinction (though football was discontinued for financial reasons, not disciplinary). The best thing – the only thing – that USF could do in order to both exhibit accountability and avoid long-term damage, was engage in self-policing. After all, when Rev. Lo Schiavo hired Pete Barry back in 1980, he wanted the new coach to be “Mr. Clean.”

USF would take the unprecedented step of shutting the program down on its own, without any outside influence from the NCAA.

That’s how it came to be that John Lo Schiavo would stand at that podium on the morning of July 29, 1982, announcing that the basketball program would be shutting down for an extended period time. The school’s eighteen-member board of trustees had voted in favor of exile a couple days earlier. It was necessary, Father Lo Schiavo said, to preserve the University of San Francisco’s “integrity and its reputation.” The program could be resurrected, he said, possibly “on a lower level,” such as Division II, “but as far as Division One, I don’t know what people will do three, four, or five years from now.”

The athletic department would be left to deal with the fallout. With no basketball for the 1982-83 season, the returning players had a decision to make: continue their educations at USF with no basketball, or continue their college hoops careers by transferring to another school. For those who remained, athletic director Bill Fusco said, “their complete scholarship commitment will be honored.” Likewise, recently graduated high school recruits who were due to enter campus in the upcoming fall would be allowed to de-commit and enroll elsewhere if they desired.

AND THERE WOULD BE A huge hole left in the campus culture.

“I think it’s a shame that the team is gone,” an unnamed USF student told UPI. “They should have gotten rid of the coaches and the president instead. I don't know what I'm going to do this winter without basketball. It was the only thing to do on campus.” Said Mark Hurd, a graduate student approached by a New York Times reporter, “Basketball is such a big thing here, I'm going to miss it. The games are a major catalyst for social activities that involve so many students.” Others, though surprised, sided with the decision. Reverend Lo Schiavo and the Trustees “probably did the right thing,” in the words of Chuck Leavitt, who worked in the school’s records department, because “[t]he integrity of the university has to be preserved” and “[i]ntegrity is far more important than basketball.” He then added, “[t]he players have been manipulated by people who want to make basketball here almost a professional thing. It’s unfortunate, especially for the players.”

Unfortunate, indeed. Only time would tell if or when the program would be relaunched, and at what level. But for now, the successful program that went to fifteen NCAA tournaments, won two national titles, and turned out the likes of Bill Russell and K.C. Jones and Mike Farmer and Phil Smith and Bill Cartwright — all in fewer than thirty years — would cease to exist, leaving a sudden, shocking, and sizeable hole in the NCAA basketball landscape.

For only three years, as it would turn out.

Next: “Part 4 - Revival” documents the program’s restart after three seasons in exile. Former Dons star Jim Brovelli would be tapped to take over as head coach, but USF basketball would tread quicksand for much of the ensuring several seasons since the three years away posed a formidable hurdle to recruiting. It would be four seasons before the Dons would finish with winnings records both overall and in-conference, and thirteen before they would return to the NCAA Tournament. To be alerted when posts go up, feel free to subscribe!

Sources:

“1974 Police Strike,” Baltimore City Police History. https://baltimorepolicemuseum.com/en/our-police/1974-police-strike.html

“A civil suit against former University of San Francisco....” UPI Online Archives, January 18, 1983. https://www.upi.com/Archives/1983/01/18/A-civil-suit-against-former-University-of-San-Francisco/2382411714000/

“Alum Turns Against USF.” San Francisco Chronicle, August 20, 1982, pg. 68.

“Settlement of Suit Against Dailey Near.” San Francisco Chronicle, January 18, 1983, pg. 43.

Boyle, Robert H. “Bringing Down the Curtain.” Sports Illustrated/Vault.SI.com, August 9, 1982. https://vault.si.com/vault/1982/08/09/bringing-down-the-curtain

Crumpacker, John. “Dailey Leads USF Past Georgia.” San Francisco Examiner, November 29, 1981, pp. C-1, C-2.

Crumpacker, John. “USF Captures Golden Gate Title.” San Francisco Examiner, December 20, 1981, pp. C-1, C-3.

Crumpacker, John. “USF Rolls to Easy Win Over Loyola.” San Francisco Examiner, January 17, 1982, pp. C-1, C-2.

Crumpacker, John. “USF Holds On To Overcome Portland, 81-78.” San Francisco Examiner, January 24, 1982, pp. D-1, D-2.

Franklin, Ben A. “Baltimore Ends Its 15-Day Strike.” New York Times, July 16, 1974. https://www.nytimes.com/1974/07/16/archives/baltimore-ends-its-15day-strike-municipal-pact-exceeds-6police.html

Jackson, Roger. “In This Case, The A Is Q.” Sports Illustrated/Vault.SI.com, December 7, 1981. https://vault.si.com/vault/1981/12/07/in-this-case-the-a-is-q-whos-the-hottest-college-guard-who-can-lead-san-francisco-to-the-ncaas-why-its-quintin-q-dailey

Jupiter, Harry. “Quintin Dailey, USF Sued by Woman He Assaulted.” San Francisco Chronicle. October 13, 1982, pg. 42.

McGrath, Dan. “Inside Basketball: Dons Sneak Preview.” San Francisco Chronicle. November 7, 1981, pg. 41.

McGrath, Dan. “Inside Basketball: The Dons Need Work.” San Francisco Chronicle. November 13, 1981, pg. 77.

McGrath, Dan. “Martens, USF Beat Gonzaga.” San Francisco Chronicle. January 23, 1982, pg. 41.

McGrath, Dan. “USF Hopes New Coach is ‘Mr. Clean’.” San Francisco Chronicle. November 13, 1980, pp. 75-76.

McGrath, Dan. “USF Probation is Official.” San Francisco Chronicle. October 17, 1979, pp. 55, 57.

Murray, William D. “Problems Force USF To Abandon Basketball” UPI (online archive), July 31, 1982. https://www.upi.com/Archives/1982/07/31/Problems-Force-USF-To-Abandon-Basketball/6493396936000/

Nevius, C.W. “B.C. Beats USF, 70-66, In NCAA.” San Francisco Chronicle. March 13, 1982, pp. 42-43.

Nevius, C.W., and Dan McGrath. “USF Giving Up Basketball – Scandals Force the Decision.” San Francisco Chronicle. July 29, 1982, pp. 1, 18.

Nevius, C.W. “School Cuts Basketball – ‘There Was Really No Choice.’” San Francisco Chronicle. July 30, 1982, pp. 1, 14.

Rizzo, Mary. “When Baltimore Was Hollywood East: Racial Exclusion and Cultural Development in the 1970s.” The Metropole. November 19, 2018. https://themetropole.blog/2018/11/19/when-baltimore-was-hollywood-east-racial-exclusion-and-cultural-development-in-the-1970s

Rodricks, Dan. “Mayor Schaefer kept it clean during dirty times.” Baltimore Sun, November 10, 2009. https://www.baltimoresun.com/opinion/op-ed/bal-op.rodricksonline1110-column.html

“Settlement of Suit Against Dailey Near.” San Francisco Chronicle, January 18, 1983, pg. 43.

Spander, Art. “Inside Basketball: Truck Key to Suns’ Fast Break.” San Francisco Chronicle, May 1, 1979, pg. 45.

Strand, Robert. “The young victim in the sexual assault case involving....” UPI (online archive), October 12, 1982. https://www.upi.com/Archives/1982/10/12/The-young-victim-in-the-sexual-assault-case-involving/8537403243200/

“Texas Takes Advantage of Dons’ Generosity.” San Francisco Chronicle, December 28, 1979, pp. 51, 54.

“USF Loses; Wichita Upset,” San Francisco Chronicle (A.P. wire), December 30, 1981, pg. 47.

Vecsey, George. “The Silent Teammates.” New York Times, August 23, 1982, pg. C9; also: https://www.nytimes.com/1982/08/23/sports/the-silent-teammates.html

White, Gordon S. Jr. “San Francisco Drops Its Basketball Program.” New York Times, July 30, 1982, pg. A15; also: https://www.nytimes.com/1982/07/30/sports/san-francisco-drops-its-basketball-program.html

Keynesians hitched their wagon to the hope that increased government spending and lower interest rates would reduce aggregate demand. They were steadfast adherents of the Phillips curve, which claimed a strong inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation; the Phillips curve took a beating in 1970s as a result of “stagflation,” in which there were high levels of both. Inflation had already been on the rise in the mid-to-late-1960s before unemployment skyrocketed from 3.5 percent to over 6 percent by 1970, peaking at 8.2 percent in 1975.

The WSU Shockers finished 23-6/12-4 and boasted four future NBA players: Antoine “Dr. Dunkenstein” Carr, Xavier “X-Man” McDaniel, Cliff “Good News” Levingston, and lanky 7-foot-1 center Greg Dreiling. Like the USF Dons, Wichita State would later be placed on probation due to the actions of their assistant coaches back in the late 1970s.

Dialogue and descriptions are from a testimony given during a closed preliminary hearing held on March 22, 1982, recreated in part in an August 1982 article in Sports Illustrated. Victoria Brick is not identified by name in the SI piece, but her identity was revealed in subsequent stories put forth by UPI and the San Francisco Chronicle, which are listed in the Sources.

San Francisco Superior Court Judge Edward Stern could have sentenced Dailey to as much as seven years of jail, but opted for probation after receiving “unsigned and unpleasant letters” in the mail.

Albert J. Zabala: https://www.ancestry.com/genealogy/records/albert-j-zabala-24-2lxqk9