The covers of this book are too far apart.

— Ambrose Bierce, short-story writer

If you can’t draw something, just draw it.

— Dieter Roth, Swiss artist

HE ARRIVED ON CAMPUS AS a freshman in 1984, the recipient of a scholarship to play on the first USF Dons basketball team since the program was reinstated from its three-year self-imposed death penalty. A six-foot-six forward, the young man played sporadically; he averaged just over six minutes a game and hit 15 of 30 shots attempted for an exact .500 shooting percentage. He also gobbled up 21 rebounds. The Dons won just seven total games that season, including two within the conference. The good ol’ days of Hilltop hardwood were a blip in the rear view, but at least the program was back.

The lanky big man – he was listed at 185 pounds – would not return after the season. Although he was a talented hooper, good enough to win team MVP and all-league honors as a high school senior, basketball became less of a priority as he immersed himself in the campus culture. Particularly, music; more specifically, he fell under the thrall of the campus radio station, KUSF. “My dorm room was right above the campus radio station,” he recalled years later. “I think I ended up spending more time listening to the radio and going into the radio station than I did on the basketball court. I just fell in love with music. [USF] was about five blocks away from Haight-Ashbury – San Francisco. So, I’d go down to Haight-Ashbury district and I would hang out with punk rockers, and hip-hop heads, and Deadheads.” He later bought a bass guitar and learned to play it, and he also took up writing poetry.

He joined his first band in 1986, a combo punk-rock and spoken-word outfit named the Beatnigs. He created another band four years later, with little success. Finally, in 1994, Michael Franti formed his most successful group, Spearhead, a band that is still going strong nearly thirty years and eleven albums later. Franti became an outspoken advocate of social justice, mirroring USF’s core values. He produced and directed his first documentary, “I Know I’m Not Alone,” in 2005, depicting the plight of people living in war-torn countries such as Israel, Palestine, and Iraq. “I wanted to hear about the war by the people affected by it most: doctors, nurses, poets, artists, soldiers, and my personal favorite, musicians,” he said.

The New Man on the Bench

JIM BROVELLI BECAME THE LATEST ex-Don player to take the reins as USF coach, joining the likes of Bob Gaillard, Phil Vukicevich, Ross Giudice, William “Tiny” Bussenius, and Wallace Cameron. A point guard under Pete Peletta from 1961 through 1964, the six-foot-one San Francisco native averaged 8.6 points per contest as the Dons won 41 of 55 games, two WCAC titles, and received two NCAA Tournament invites. Brovelli went undrafted and no professional basketball team so much as sniffed him. His days in the game appeared to be over.

Not quite. Brovelli stayed in the city and soon became the head basketball coach at Lick-Wilmerding High School. Seven years later, in 1972, he became an assistant under Jack Avina at the University of Portland. After a single season in the Rose City, Brovelli was summoned down the coast to the University of San Diego, at the time a Division II school. Brovelli would transform the Toreros basketball program into a run-and-gun powerhouse within five years, and he successfully lobbied the school’s leaders to upgrade the program to Division I status in time for the 1979-1980 season. Although USD struggled in those early years in NCAA’s highest tier, they continued to improve, culminating in a successful 1983-84 season in which the Toreros, led by a trio of forwards in Mike Whitmarsh (18.8 PPG), Anthony Reuss (11.7), and Mark Bostic (10.2), won the WCAC with a 9-3 record and earned the program’s first NCAA Tournament bid. The Toreros lost to Pete Carril’s Princeton Tigers in the opening round in what would be Brovelli’s final game with USD. With the Dons resuscitating basketball for the 1985 season, they needed a coach who could take over well in advance and lay the groundwork to rebuild the program out of thin air. Brovelli checked two big boxes: one, his ties as a local kid who had played at the school; and, two, his remarkable success in building up USD. He would need every bit the patience and determination he displayed over his eleven years with the Toreros to turn the New Dons into anything faintly resembling the competence of the pre-Death Penalty Dons.

The hiring was made official on April 5, 1984, with Brovelli inking a five-year pact.

The Aftermath

THE WEEKS, MONTHS, AND YEARS following USF president Rev. John Lo Schiavo’s fatal July 1982 announcement featured significant fallout.

On October 12, Victoria Brick filed a lawsuit against Quintin Dailey and the University of San Francisco. Now twenty-two and working as a nurse in the East Bay, the USF grad’s suit targeted the ex-Don for his assault on her back in December 1981, as well as the school for refusing to pay her $125,000 as a share of an out-of-court settlement in August. In the suit, she accused USF and the school’s director of public safety, Sviatoslav “Yash” Yasinitsky, for “conspir[ing] to obstruct justice and cover up the identity of Dailey.” Rev. Lo Schiavo’s response was that there was, according to university lawyers, no basis for a claim against the school.

SHORTLY AFTER THE ATTACK, YASINITSKY had interviewed both Brick and Dailey separately. According to Yash, Dailey “appeared to know nothing about this incident [that] was not revealed to him, except in general terms. He appeared to have had a sober countenance, and otherwise showed no reasons to suspect him as the above[-named] intruder.” The ex-Don star told the public safety chief that he was changing rooms on the night in question and with the assistance of teammate Eric Booker was moving from Phelan Hall’s fifth floor down to the second. Dailey told Yasinitsky that he fell asleep in his new room at 2:30 in the morning, then woke up several hours later. Yash related that “[Dailey] behaved bewildered about my questioning. I said a woman had been molested. He sprung up and said, ‘I don’t need to rape anyone.’”

Then, at five o’clock, Yash spoke to Victoria Brick for a second time, and told her that he was siding with Dailey, believing the young man was innocent. He “warned” her that a court case against Dailey would be dubious at best, due to a lack of physical proof. The paucity of evidence, however, was Yasinitsky’s fault. A twenty-seven year veteran of the San Francisco Police Department, Yash should’ve known enough to photograph the bruises and marks on Victoria’s body; he should’ve had the presence of mind to secure the bedsheets with the ejaculate on them in order to extract a blood type; and he had failed to dust Brick’s dorm room for fingerprints (he claimed that only the telephone, which Dailey had not touched, had a surface that could yield prints). The ex-cop did none of those things.

Six weeks later, Yasinitsky and a lawyer corralled Charlie Reynes, the nearly blind residence assistant who had chased Dailey out of Victoria’s dorm room mere minutes after she had escaped. The two men “brought me down and showed me pictures of Black guys and had me listen to voices. Yash told me it couldn’t be Quintin Dailey. It seems like they had to handle the case with kid gloves, but their gloves were awful soft.” During his interview with Yasinitsky, Reynes recalled an incident the previous year when another USF basketball player, 7-foot-2 center Rogue Harris, attacked him in his room, then “ripped a couple of buttons off my shirt, threw me on the bed, and said – [and] there were two other people in the room – that if they moved they were dead, he’d kill them.”

“Some of the players they recruit are not outstanding,” Reynes said later. “They are not interested in going to school. There is very little discipline at USF for basketball players. It’s sick, and this is my alma mater.” He elaborated that Yash didn’t report the Harris incident to SFPD because “if the police were brought in there would be headlines the next day because Rogue’s a basketball player.”

Even if Victoria Brick couldn’t 100 percent identify Quintin Dailey as her assailant in those early morning hours of December 21, 1981 – she had told Yasinitsky that she had “a five-percent doubt” (though she later testified to calling Quintin by his name when he first entered her room) – she certainly had a case that USF’s head of public safety was not bereft of dedication when it came to protecting the school’s basketball players.

She eventually received a settlement from the university for less than $100,000.

IN 1984, PETER BARRY, THE final head coach in the program’s pre-exile history, filed a libel suit against Sports Illustrated1, with Dailey named as an additional defendant. Barry’s complaint regarded the magazine’s assertion that, according to the suit, “Barry had actually transferred money improperly to USF basketball players, and that Sports Illustrated’s report of a ‘scandal’ and ‘shocking conditions’ in the USF basketball program led readers to accept as true the assertion that Barry had been involved in improper payments to basketball players,” and, further, that “Time [Sports Illustrated’s parent company] was at least negligent in failing to exercise reasonable care to discover the falsity of the assertions contained in the articles. Moreover, it is alleged that the articles were published either with knowledge that they were false or with reckless disregard of whether they were false. Since the articles mention that Dailey was a convicted felon and had failed a polygraph test regarding the assault to which he ultimately pled guilty, it is claimed that Time subjectively entertained serious doubts as to the truth of Dailey's assertions that Barry improperly transmitted money to him.”

Barry claimed that the statements made by his former player were preventing him from getting another coaching job. He had sent out forty applications, he said, but “I’ve been interviewed at only one college.” However, the suit dragged on with no advancement, and in late January 1985, Barry withdrew it.

The ensuing few years were not kind to the man who, rightly or wrongly, was stigmatized by the twin revelations of Quintin Dailey assaulting a coed and accepting illegal cash, (including possibly from Barry himself). More job applications resulted in rejection. His wife left him, and he was forced to sell the house. He accepted work as a substitute teacher, a high school baseball coach, and bartender just to pay the bills. But coaching basketball at the University of San Francisco gave him a sense of self-worth that he had struggled to maintain after the program was dissolved. “There were some trying times,” he said. “I was in the right place at the right time when I got the USF job, and the wrong place at the wrong time when I lost it.” Barry eventually latched on at Southern Oregon State College (now Southern Oregon University), in Ashland, Oregon, located just thirteen miles south on Interstate 5 from Medford, where he had once played minor-league baseball. Barry led the Southern Oregon Raiders for six seasons, amassing a .549 winning percentage.

Speaking in 1985 about his decision to drop the lawsuit against Sports Illustrated and Quintin Dailey, Barry cited his desire to put his USF troubles behind him. “If I’d been unemployed or in the frame of mind I was in maybe a year ago, I’d have pursued it,” he said. “But I want to put that chapter of my life behind me. I can’t be worried about Quintin Dailey’s problems.”

BACK ON CAMPUS, REV. LO SCHIAVO also had to deal with shrapnel hurtling his way. The most aggrieved were the boosters, who took umbrage with the school president’s decision to terminate the basketball program, the travel and recruiting restrictions placed on the soccer team, and the discontinuation of the independent Dons Century Club in favor of a campus-controlled booster group. “The boosters claim Lo Schiavo is moving toward virtual abandonment of intercollegiate athletics,” reported the Chronicle, “[a]nd … he tolerates no opposition to his decisions, having insulted two long-time USF supporters who voiced their disagreement publicly.”

The two supporters were Steve Chapralis, an alumnus and a member of the Century Club working as an accountant in suburban Daly City; and former USF baseball coach (1962-1980) Dante Benedetti, whose family owned the New Pisa restaurant on 550 Green Street in the North Beach neighborhood2. Chapralis was the author of a scathing letter to a newspaper criticizing Lo Schiavo’s decision to drop basketball, and he had also co-signed a letter to the USF Board of Trustees that condemned Lo Schiavo’s “arbitrary, autocratic decision-making.” On June 17, 1983, Chapralis spotted Lo Schiavo having lunch at the Olympic Club, and approached him to offer congratulations on restoring the basketball program. Upon recalling Chapralis’s earlier denigration, the school president’s smile morphed into “an icy stare” and he barked out “Up yours, Steve. And if I never see you again it will be too soon.”

Benedetti found himself in Lo Schiavo’s crosshairs after giving a “strongly worded, impromptu speech rejecting a suggestion that his monthly USF luncheons become functions of the Green & Gold Club,” the new booster group that replaced the Century Club. Lo Schiavo told Benedetti that he would “never set foot in [his] restaurant again.” The two later made amends.

Peter Barry also had his issues with the Lo Schiavo administration. After the school dropped basketball, the coach filed for unemployment compensation, only to have it contested on the grounds that “he’d violated his contract by breaking NCAA rules.” Barry eventually won his claim after a hearing took place and no one from USF bothered to show up. “I don’t think Father Lo Schiavo understands the alienation that’s taken place,” he said. “It’s almost like he’s on an arbitrary, personal vendetta because of the bad publicity surrounding the Quintin Dailey legal problems.”

The Green & Gold Club was also a source of some consternation. “The boosters don’t see their place in the new program,” reported the Chronicle. “In August [1983], Century Club members received a letter from USF vice president Alfred P. Alessandri inviting them to join a newly formed, ‘official’ booster group, the Green & Gold Club. The letter said the new club would be the sole channel for funds raised by athletic boosters.

“Club members tested the new policy, sending USF a $500 check for soccer. The school sent it back.”

Then there was J. Luis Zabala, the booster from Salinas who had given Dailey money for working the no-show job, and who years earlier had been Father Lo Schiavo’s classmate and basketball comrade St. Ignatius. In August 1982, mere weeks after the decision to drop basketball, Zabala went to court to have USF removed from a trust-fund agreement that his parents had initiated back in 1960. Under the agreement, all income and interest derived from the family’s long-held Monterey County ranch land would be bequeathed to the school upon the deaths of Zabala and his five children. For his part, Zabala claimed that the removal was “agreed to several years ago,” although the timing of it appeared to suggest otherwise. By that point, Zabala and Lo Schiavo were no longer on speaking terms. “He knows my first name, my last name, and my telephone number, but I have not heard from the good Father,” Zabala said. “The silence is deafening.”

Zabala died in 2009. According to his obituary3, he had established a scholarship fund at Chaminade University of Honolulu.

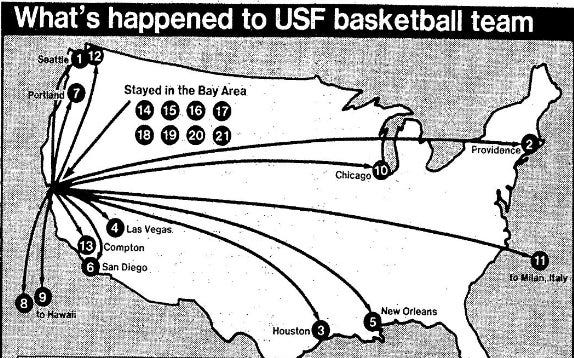

THE BASKETBALL PROGRAM’S SHUTDOWN SCATTERED members of the 1981-82 team to the four winds. Some were drafted into the NBA, others graduated and began their post-collegiate lives, and still others transferred in order to continue their hardwood careers. A few stuck around.

Sophomore reserve guard Crosetti Speight, who averaged nearly 12 minutes per game for the 1981-82 Dons, transferred to the University of Hawaii, as did Charlie Reynes’s dorm-room assailant, center Rogue Harris. Eric Booker transferred to UNLV, where for two seasons he helped Jerry Tarkanian’s squad win the Pacific Coast Athletic Association (PCAA)4 title; the 1983-84 Rebels went all the way to the Sweet Sixteen before falling to eventual champion Georgetown. Freshman forward John Martens headed to San Diego State, where he would stay for four years (a knee injury suffered during his junior year resulted in an extra year of NCAA eligibility). Backup center Farley Gates, also a freshman, ventured out to the Big Easy and Tulane University; he seldom played and never traveled with the team. The San Diego Clippers drafted John Hegwood, but he never signed. Lamar Baker, a transfer from City College of San Francisco who would have suited up for the 1982-83 season, decided to head across the Bay to the University of California but he couldn’t gain admission. David Boone, a forward, was recruited to USF as a freshman and ended up across the Bay at St. Mary’s. Three other incoming freshmen -- Paul Fortier, Renaldo Thomas, and Donnie Brown -- also ended up at Division I schools. A trio of little-used reserves, Vladimir Jacimovic, Robbie Lowry, and Jimmy Giron, elected to remain at USF. Ken Smith, one of Peter Barry’s assistants, also remained on the Hilltop, and was put in charge of the intramural team, which consisted of Lowry and Giron.

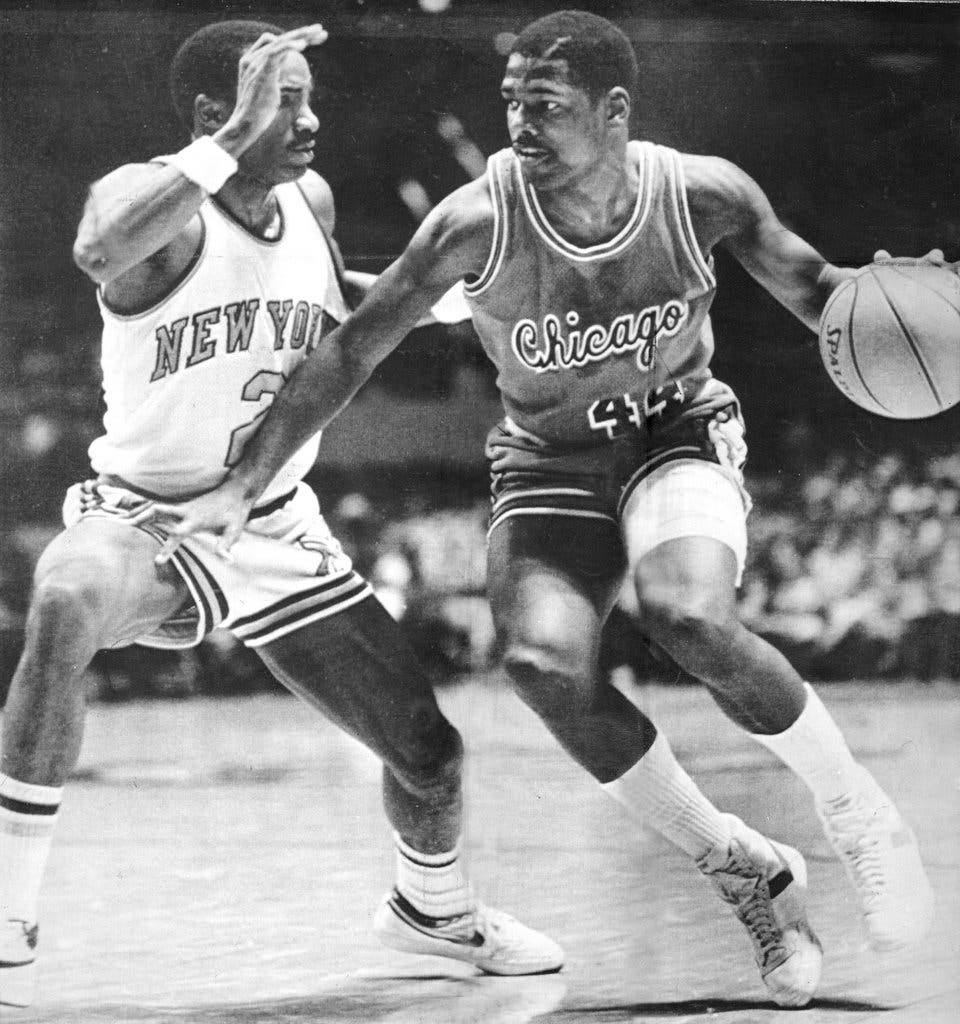

The Chicago Bulls drafted both Quintin Dailey (junior5) and Wallace Bryant (senior), in the first and second rounds, respectively. Bryant’s NBA stay was a short three years, bouncing from the Bulls to the Dallas Mavericks and finally to the Los Angeles Clippers, with whom he played just eight games. He began a second career playing international ball, suiting up for teams in Spain, Italy, and Argentina before hanging the sneakers up for good in 1997 at age thirty-eight.

Dailey’s NBA career was longer and more fruitful, but also controversial. Women’s group protested his arrival in Chicago, and he initially struggled to find suitable housing due to being turned down at every apartment complex he applied to. Nonetheless, Dailey broke out in his second season in the Windy City, averaging 18.2 points per game for a bad Bulls team. But, come his third season, Dailey had to contend with a flashy rookie from the University of North Carolina named Michael Jordan. Dailey couldn’t stand Jordan and was incensed when the kid took his job as the Bulls’ starting 2-guard. Then, in a three-part profile that appeared in the Arlington Heights (Ill.) Daily Herald, Dailey took head coach Kevin Loughery and assistant coach Fred Carter to task, claiming they were “yelling at me about taking crazy shots” and accusing them of double standards, relaxing the rules for the likes of Jordan, Orlando Woolridge, and Steve Johnson while ruling Dailey and the others with an iron fist. “I definitely don’t think there are two sets of rules for people,” general manager Rod Thorn said at the time. “Dailey doesn’t take any criticism well. You can pat him on the back 85 times and yell at him once, and he’d remember the time you yelled at him.”

Regarding the Dailey-Jordan dynamic, Loughery recalled years later that Dailey “couldn’t accept Michael, honestly. Michael came in and got all the attention, deservedly so, and [Dailey] couldn’t accept it.” Angry at Jordan, angry at his coaches, and tired of people bringing up his past, Quintin had also developed a drug habit (he violated the league drug policy twice) and his behavior grew erratic, often missing practices and games and putting on weight. He also attempted suicide. “I had to learn life by trial and error as I went along,” he told the Los Angeles Times in 1988. “I erred a lot.”

Dailey lasted ten seasons in the NBA but never stuck around long with any one team. The Bulls severed ties in 1986, and Dailey eventually signed with the Los Angeles Clippers, with whom he appeared in 185 games across three seasons. He then joined the cross-town Lakers as a free agent. But Dailey never suited up for the Lakers, and soon he was on his way to Seattle. Quintin sporadically played in two seasons with the SuperSonics and was waived on December 10, 1991. His NBA career was over at age thirty, but he was also clean and sober.

Dailey moved his wife and their two children, son Quintin Jr. and daughter Quinci, to Las Vegas, where the former basketball star began a new life mentoring troubled youth at the Boys and Girls Club and volunteering at a senior citizens center. But he also had a fondness for fast food, became overweight, and soon developed high blood pressure. Quintin Dailey died in his sleep on Monday, November 8, 2010, a little over two months shy of his fiftieth birthday.

PERHAPS THE MOST INTERESTING POST-USF journey belongs to Ken McAlister. The 6-foot-5 guard had been a standout in both football and basketball at Oakland High School, and though several high-profile football schools, including UCLA, USC, and Notre Dame, were recruiting him for the gridiron, McAlister opted to play hoops on the Hilltop. McAlister’s graduation from USF coincided with the end of the basketball program, and he got no offers to play professionally. Still feeling the pangs of competition, McAlister decided to give football a second try, trekking north to Seattle Seahawks training camp in Cheney, Washington, a tiny town of about 7,700 located sixteen miles southwest of Spokane. “Here’s me, I haven’t put on a [football] uniform in four years,” McAlister said. “It’s 102 degrees in Cheney … and I wondered what I was doing.” A linebacker in high school, McAlister was shifted to safety, where he struggled to learn the terminology. It mattered little, though, as he wound up serving on the Seahawks’ special-teams units. The Seahawks waived McAlister in 1983. He returned to San Francisco and attended a tryout with the 49ers, eventually signing on for the rest of the ‘83 season. The Niners opted to not bring him back. McAlister then spent three seasons with the Kansas City Chiefs. His first year in K.C. was his best, as he hauled in a pair of interceptions for a total of 33 yards, recovered one fumble, and recorded four quarterback sacks. His second and final interception, on October 28, 1984, against the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, came at the expense of quarterback Steve DeBerg, an erratic former 49er known for tossing the ball to the other team.

Putting the Past In the Rear View

“WHAT HAS HAPPENED HERE, HAS happened,” Jim Brovelli said at his introductory press conference on April 5, 1984. “We can’t change that. It’s over with. I’m not really concerned about that, and I don’t think any recruits should be concerned about that. I’m interested in now and the future. We’re starting a brand new program.

“We still have that great tradition,” he continued, mindful of his own past as a USF star player of yesteryear. “That never left here.”

But Brovelli would have to contend with several guidelines that would shape the basketball program’s rebirth. Recruiting was to be limited to west of the Rocky Mountains, there would be only twelve scholarships available, and a local emphasis for scheduling was required. Further, there would be stricter academic standards for players and a new alumni group, the Green & Gold Club, which would be overseen by the school. “I think [the guidelines] are a blessing,” Brovelli said. “The university now has control of the program. I’m for that 100 percent.”

The forty-one-year-old also cautioned against heightened expectations. “No questions, there’s going to be growing pains. If everyone expects to do it the first year or the second year, I think they’ll be disappointed.”

Touché. Brovelli’s initial roster figured to be primarily freshman whom he could convince to join with the promise of immediate playing time, but not necessarily the most talented players available. The greenhorn cast would be augmented by “[t]wo, possibly three [junior-college transfers] at the very most,” though not heavily relying on those two-year players, since they don’t provide “that long-term continuity you look for.”

One of his first recruits was the future musician Franti, who was born in Oakland but went to high school in the agricultural town of Davis, fifteen miles outside of Sacramento. Another was Peter Reitz, a six-foot-eleven center who transferred from the University of Idaho but hailed from Auburn, roughly thirty-five miles outside of Sacramento. Three more soon followed, giving Brovelli at least enough to field a starting lineup: Robbie Grigsby, a guard from Lincoln High in San Francisco; Darrell “Sky” Walker, a six-five combo guard-forward from Long Beach, California; and forward Anthony Mann, a six-foot-seven transfer from West Valley Junior College in Saratoga, southwest of San Jose.

A murderer’s row, it was not. Mann’s 10.4 points per game paced the 1985-86 Dons, who won just two conference games and seven overall. The WCAC was ruled that season by the Pepperdine Waves, who blasted their way to a 13-1 conference record for their fifth conference title in the seven years since Jim Herrick became their head coach. Second-place Loyola Marymount, thanks to their new head coach Paul Westhead, executed a beautiful U-turn from their dreadful 11-16/3-9 mark from the year before, finishing three games behind Pepperdine. Although the losses of senior stars Kevin Smith and Forrest McKenzie to both graduation and the NBA plundered the Lions back to the dregs the following year, it was an ephemeral dip, as Westhead turned the program back around and LMU finished the 1980s with three straight NCAA tourney appearances, spurred by the stellar play of future pros Bo Kimble and Corey Gaines, as well as outstanding forward Hank Gathers6 and guard Jeff Fryer. Pepperdine fell off a bit for a couple of seasons, and in 1988 Herrick departed to take over at UCLA, where he had previously worked as an assistant. Under new head coach Tom Asbury, the Waves regained their footing and posted five straight 10-win seasons in-conference, making the NCAA Tournament three times in a four-year stretch.

WHILE THE LOS ANGELES SCHOOLS were cavorting atop the West Coast Conference7 table in the mid-to-late Eighties, the USF program struggled to recapture its past glory, which seemed to grow further and further away with each passing, agonizing year. Recruiting and building off prior success is key in college basketball, and it was something that the Hilltoppers had done well for three decades. The achievements of the Bill Russell-K.C. Jones-Mike Farmer Dons, culminating in back-to-back national titles in 1955 and 1956, gave way to the strong Ollie Johnson-Jim Brovelli-Joe Ellis teams of the early- and mid-1960s. Although the Phil Vukicevich teams of the late Sixties were a bit of a fallow period – the Dons failed to win more than nine conference games in Vuke’s tenure – there were still bright spots, such as forward Dennis Black and volume-scoring center Pete Cross8. The Phil Smith-Kevin Restani-Eric Fernsten Dons of the early 1970s under Bob Gaillard brought the program more NCAA tourney bids and paved the way for the great Bill Cartwright-Winford Boynes-Marlon Redmond-James Hardy squads, then, finally, the Quintin Dailey-Wallace Bryant teams. From 1970-71 through 1981-82, the Dons won eight WCAC titles and went as many NCAA Tournaments. In those twelve seasons, USF won 20 or total games nine times and flashed double-digit conference victories in all but two. If the Dons weren’t in first place, then they were obdurately nipping at the heels of whoever was ahead of them. Wrote C.W. Nevius of the San Francisco Chronicle in 1995, “USF won the national championship, appeared on the cover of Sports Illustrated more than once and generally took over the city. In those days, an NCAA Tournament invitation was never a question. The payoff for a first-round game was built right into the basketball budget. It was a given.”

The momentum was building, building, building towards a long, fruitful period of success to come.

And then it vanished. There would be no Hilltop hoops for three whole seasons.

The chain was broken.

And now Jim Brovelli had the unenviable task of resuscitating the program. No longer could the University of San Francisco rely so much on its past as a means to attract top-notch basketball recruits. Brovelli’s introductory remark about “that great tradition” technically wasn’t wrong. But spiritually, his words rang a bit hollow, and, over time, proved to be far too optimistic. In the What have you done for me lately? milieu of high-profile NCAA Division I athletics, the USF Dons could merely shrug and point to a three-year basketball void (besides the intramural squads that ex-assistant Ken Smith was in charge of). Yes, there was tradition: Dailey and Bryant and Cartwright were playing in the National Basketball Association, and a few older Dons of yore – Fernsten, Smith, Restani, Hardy, John “Chubby” Cox – had recently seen their NBA careers end. But three years in the wilderness ensured that the University of San Francisco men’s basketball program was no longer a preferred choice for talented high school kids who wanted to play where they could be discovered by pro scouts. If you wanted to play on the West Coast and felt ignored by the big schools in the Pac-10, then the WCAC’s two teams in Los Angeles were the better places to go. Not surprisingly, Pepperdine (which is actually located not in L.A., but in nearby Malibu) and Loyola Marymount rose up and filled the space left behind by USF’s absence.

BROVELLI GAMELY HUNG ON TO the job for ten seasons, and the Dons endured losing records in six of them, never winning more than eight conference games. The restrictions placed upon Brovelli right out of the gate didn’t help, and the school didn’t provide him with the resources required for recruiting or even a staff. “Actually, it wasn’t that bad,” cracked the Chronicle’s Nevius. “If you broke the budget down to quarters, you could make 10 or 15 phone calls a day.”

The Brovelli era did have its highlights. On January 7, 1989, the Dons defeated Notre Dame 79-75 in front of a raucous sellout crowd of 5,370 at War Memorial Gymnasium. The Fighting Irish were bigger; the Dons were faster, winning the game despite being out-rebounded 37-22. They also sunk 25 of 33 free throws, compared to just 12 of 19 for Notre Dame. Senior center Mark McCathrion dropped in 26 points, many of which came at the expense of the Irish’s LaPhonso Ellis, who would later go on to play eleven seasons in the NBA.

Digger Phelps was agitated. The longtime Notre Dame head coach’s sour maw wasn’t foamy because of losing to USF, per se. He was mildly nettled by the officiating, citing the free-throw disparity, and he also had some less-than-flattering remarks about the building itself. “It was like a Sunday afternoon CYO League game back home in New York,” Phelps snapped. “Our freshmen thought we were playing in a high school game.” It was the first time Digger had brought a team into War Memorial; past Dons-Domers matchups played in the Bay Area were staged at the much larger Oakland Coliseum Arena, home of the NBA’s Golden State Warriors. The Fighting Irish were not prepared for a cramped facility with fans close enough to the floor that you could smell the mustard stains. “We’re an upstart program,” Brovelli countered. “We started from zero four years ago. One of our goals has been to schedule teams like Notre Dame who are nationally ranked and recognized.” An intimate setting such as the “barn-like echo chamber … noisy, claustrophobic bandbox,” (as Nevius characterized it) perched on the north side of main campus was as good as any place.

The victory over Notre Dame failed to catapult USF to greater heights, however, as the Dons proceeded to drop four of their next seven games. Overall, the 1988-89 season wasn’t a bad one, as the Dons finished 16-12 overall, 8-6 in-conference, placing behind the quietly ascendant St. Mary’s and the two L.A. schools. But top-scoring seniors McCathrion (who would go into the USF Hall of Fame in 2010) and Kevin Mouton graduated after the season, and without their contributions, the Dons plunged down to sixth place in the eight-team, rechristened West Coast Conference in 1989-90. Although they showed brief spurts of competence, Brovelli could never get the Dons over the hump, and on May 7, 1995 he announced his resignation. Preseason favorites to win the conference, USF had just wrapped up a lousy 10-19/4-10 campaign, dropping 10 of their final 12. Undoubtedly, there had been speculation that the coach’s job was in jeopardy, but Brovelli insisted it was his decision, citing a recent diagnosis of high blood pressure and his desire to transition into the less-stressful career field of athletic administration, which he fulfilled by taking the vacant associate director job on the Hilltop.

Return to the Tourney

OVER TEN SEASONS, PHILIP MATHEWS had compiled an astounding 298-56 record at Ventura Community College, winning a pair of California Community College Athletic Association (CCCAA) titles. Six times the Pirates won 30 or more games, including an eye-popping 37-1 in 1994-95.

Mathews, forty-four and the son of an Air Force master sergeant, was an intense, take-no-shit kind of coach. He didn’t make a habit of chewing out officials or spewing invective during press conferences. But he was a hard worker who demanded the same effort from his players, and goddammit, you had better work your ass off for the professors, too. “It’s about going to school,” Mathews insisted at his introductory press conference on July 11, 1995. “You’re here to do the best you can in the classroom, and basketball – it’s part of your life. And I expect you to do both very well.” Mathews was unafraid to dismiss players – even star players – for slacking off in their studies. One of them was Rafer Alston, who subsequently transferred to Fresno City College and then to Fresno State before embarking on an eleven-year NBA career. Several years earlier, Mathews suspended Calvin Curry for a year “after repeated warnings” for truancy.

Mathews also promised an up-tempo style of basketball, similar to Paul Westhead’s run-and-gun at Loyola Marymount. And he pledged to get the Dons back into the NCAA Tournament. “I’m a very adaptable guy,” he added. “But you’re going to do it my way [emphasis added]. There are some players who aren’t going to do it your way. And there’ll be a parting of the ways. That happens in any business.

“But I don’t anticipate that.”

MATHEWS GRADUALLY BUILT UP THE roster, adding the likes of Hakeem Ward and Damian Cantrell as transfers and recruiting local kid Ali Thomas, a sharp-shooting guard, from the hallways of St. Ignatius High. His efforts culminated in a very respectable 19-11 overall record, but with a mediocre 7-7 conference record that was good for just fifth place, yet only three games behind front-running Gonzaga in a crowded WCC. But then the Dons achieved the unexpected: they won the WCC Tournament, taking down St. Mary’s, Santa Clara, and Gonzaga to earn the automatic bid into the Big Dance. Unfortunately, the Dons were not long for the tourney, falling to Rick Majerus’s 30-4 Utah Utes by 17 points.

That would be the last time the Dons would make the tourney for nearly a quarter century.

THE DONS’ NEXT - AND LATEST - tourney appearance came twenty-four years and five days later, March 17, 2022, when they fell in the first round to the Murray State Racers 92-87. Graduating fifth-year senior Jamaree Bouyea, who would go undrafted but sign on with the Miami Heat’s developmental team, led all scorers with 36 points. The game was held at Gainbridge Fieldhouse in Indianapolis, and, owing to the powers of modern technology, it was streamed online to a few hundred spectators inside War Memorial Gym, who craned their necks to view the happenings in the Midwest on one of the new videoboards placed in each of the building’s corners. (In another major upgrade, the upper west side stands were converted into the Sobrato Club9, a members-only viewing area consisting of luxury seating, all-you-can eat food, and high-end alcohol, privileges that one can purchase starting at $1,500 per year.) The Dons were helmed by thirty-seven-year-old Todd Golden, a three-year starting guard at St. Mary’s, who came to the Hilltop in 2016 as an assistant to Kyle Smith, who was tasked with stabilizing the program after the tumultuous Rex Walters years. When Smith departed after the 2018-2019 season, Golden succeeded him. It was during this “Golden era” that the new club and scoreboards were added; then, just one day after the Murray State loss and without warning, Golden took the vacant head coach position with the University of Florida. Chris Gerlufsen, nine years Golden’s senior and his top assistant since 2021, became his successor.

From the Bayou to the Bay

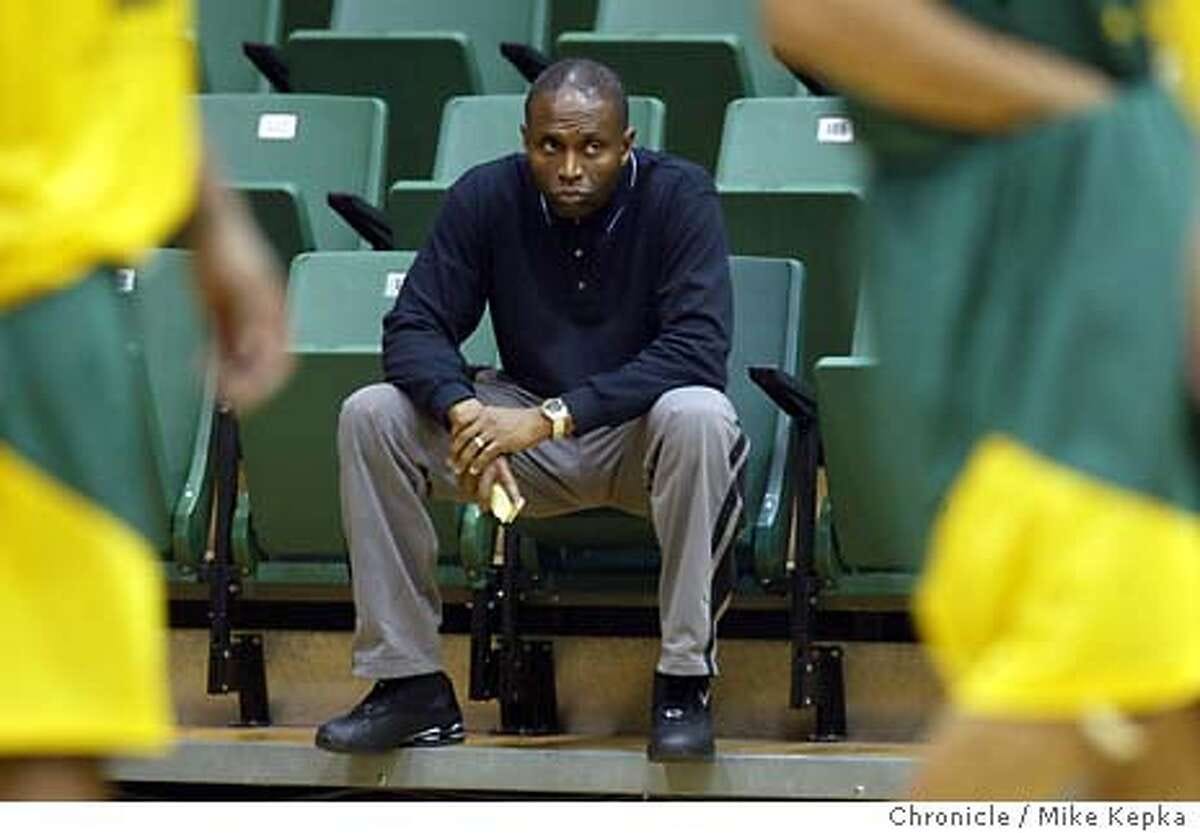

A LOT HAD HAPPENED DURING that quarter-century interregnum between tourney appearances. March 8, 2004, brought news of a bombshell announcement: Phil Mathews had been fired despite having a year remaining on his contract. No one was more surprised – and displeased – than Mathews, who felt blindsided by athletic director Bill Hogan. Hogan had pointed to the accomplishments of a pair of other small Jesuit schools: conference-mate Gonzaga, and Philadelphia-based St. Joseph’s of the Atlantic 10. Both were ranked in the top 3 and were coming off undefeated seasons within their respective leagues. The USF A.D. wanted nothing more than for the Dons to emulate both the Zags and the Hawks10. For his part, Mathews was unaware of such lofty expectations. “If I was given the proper resources, like St. Joe’s and Gonzaga, and given a chance to do that, it would be a different story,” he said. “We don't have the facilities and we don't have a full staff. We don't have any of that.”

“I’d been told ‘you have to win,’” Mathews added. “That’s told to every coach. I thought I did that [his last Dons team finished 17-14/7-7]. I also thought people look at different circumstances -- losing your best player and things like that.”

There was no shortage of possible replacements floating around. Dons legend Bill Cartwright was one such name; he had just been fired as the Chicago Bulls’ head coach less than four months earlier. Also considered were a lesser-known trio of former USF players -- Kevin Mouton (head coach at Oregon State), Rodney Tention (assistant at Arizona), and Bill Carr (assistant at Long Beach State, former Don assistant). Steve Lavin, the deposed UCLA-gaffer-turned-ESPN-analyst, was another possibility; his father, Albert “Cappy” Lavin, played for both Pete Newell and Phil Woolpert on the Hilltop. The biggest fish in the pond, however, was legendary Purdue head coach Gene Keady, known as much for his comb over as his success on the sidelines. The sixty-seven-year-old seven-time Big Ten Coach of the Year interviewed with Hogan, but he opted to remain at Purdue (after his contract ended in 2005, he joined the NBA’s Toronto Raptors as an assistant).

In April, Hogan finally found his replacement. Jessie Evans, fifty-three, had been the head man at the University of Louisiana-Lafayette for seven years, racking up a 315-177 record and four Sun Belt regular season championships, winning the conference’s tournament twice and even taking the Ragin’ Cajuns to a pair of NCAA Tournament appearances. He also took on several players who were academic risks and in danger of losing their athletic eligibility and successfully got them on the right track. But there were problems, too. The Cajuns had been under NCAA investigation and received two years’ probation when it was revealed that a player had suited up for Evans while academically ineligible.

Before his stint on the Bayou, Evans spent a decade in the desert as Lute Olson’s chief recruiter at the University of Arizona, signing nearly twenty players who would make the jump from Tucson to the NBA. Strong recruiting record, solid coaching pedigree, ability to mentor young men: Jessie Evans checked three very important boxes. He would be the man to lead the USF Dons in the new century, and win 20-plus games every season, reach the NCAA Tournament most years, and…

He lasted three years and change.

Evans’s first Dons team won just 17 games and had a losing conference record. His 2005-06 squad finished the season losing five of its final eight games. The next year, the Dons managed an 8-6 record against the WCC, good enough to barely finish in the top half, but they had a losing overall record. After going 4-8 to begin the 2007-08 campaign, Evans met with athletic director Debra Gore-Mann (who had succeeded Bill Hogan in 2006) and soon became the first Dons head coach to depart during a season since Phil Vukicevich resigned in 1970. Depending on who you talked to, Evans either requested a leave of his own volition or was presented a new twist of the old resign-or-be-fired Hobson’s choice. In taking the voluntary-absence route, Evans retained his salary for the rest of the season.

An Unexpected Interim Reaches a Milestone

TO FINISH OUT THE SEASON, USF turned to a retired legend from elsewhere. Eddie Sutton began his college head-coaching career in 1966, having founded the basketball program at space-grant community college Southern Idaho. Four years later, he jumped to Creighton, then moved on to Arkansas before spending a few turbulent seasons as Kentucky’s head coach, ultimately resigning under pressure and giving way to Rick Pitino in 1989. Sutton was highly successful during those many years, winning seven conference championships, five conference tournaments, and taking teams to the NCAA tournament twelve times. But, like USF a decade earlier, the Kentucky Wildcats men’s basketball program found itself in hot water11 and nearly suffered a death penalty of its own. Eddie Sutton was given the chance to resign rather than be fired, an option he accepted with some alacrity.

After a year away from coaching, Sutton began what would become his most successful tenure. In sixteen years as the head man at Oklahoma State University, Sutton went 368-151, winning the Big 8/Big 1212 regular-season championship twice, the conference tournament thrice, and making the NCAA Tournament in all but three years, reaching the Final Four twice. Nine of his teams finished in the Associated Press Top 25, including a pair of top-10s. His downfall began in February 2006, when, following a car accident, he was found to have driven under the influence of alcohol13. Four days later, Sutton announced he would take a leave of absence from OSU, turning the Cowboys over to his son, Sean, an assistant coach who had played under his father at both Kentucky and Oklahoma State. On May 19, 2006, he resigned. A septuagenarian, Sutton’s departure was effectively a retirement. No other school would want any part of an old geezer coach – even a successful one – with a history of alcohol problems (though he did seek treatment after leaving the program).

Well.

Except USF.

Needing someone experienced to calm the seas after Evans’s departure, USF pulled Sutton – now clean, sober, and seventy-one – out of mothballs for the balance of the 2007-08 season before seeking a younger, splashy, permanent replacement. It made for a strange union: Sutton’s coaching career was largely at large Southern schools, though Omaha-based Creighton University, where he had worked in the early Seventies, was also a Jesuit school. Sutton had never so much as stepped foot on the USF campus, and the only player on the roster he was familiar with was sophomore forward Dior Lowhorn, a San Francisco kid who had played for Bobby Knight at Texas Tech two years earlier, Sutton’s final season at Oklahoma State.

The other subplot was Sutton’s career win total. By the time he resigned-retired from OSU, Sutton had amassed a total of 798 victories. Only four other coaches had reached the eight-century mark in the history of NCAA men’s basketball: Jim Phelan, Dean Smith, Adolph Rupp, and the aforementioned Knight. Here, he had a chance to become number five, then he could head back into the comfortable cocoon of retirement as a member of an exclusive club.

It took Sutton three weeks to reach No. 799, as the Dons dropped the first four games that they played under him (extending a losing streak that began under Evans to seven). On January 19, 2008, at the Chiles Center, the Dons eked out a one-point victory over the Portland Pilots. After losing three in a row, including two straight at War Memorial, USF traveled to Pepperdine. The Dons were down by 12 points at halftime and later saw the deficit balloon to 19. Then they went on a run, tying the game at 77 apiece with just over four minutes to go. Finally, with the teams tied at 82 with 20 seconds remaining, senior forward Danny Cavic stole the ball and dropped in a 3-pointer to give the Dons the lead.

And Eddie Sutton his 800th victory.

That would be the last real highlight of the season. The Dons dropped five of their final eight games to finish the schedule.

Inconsistencies and Turmoil

THUD! THUD!

THUD! THUD!

THUD!!!

That was a constant part of the USF basketball live experience during the Rex Walters years: the steady drumbeat of free-throws hitting the rim and deflecting defiantly to the floor. In 2008-09, Walters’s first year on the Hilltop, the Dons converted from the stripe 69.4 percent of the time. Not great, but the percentages grew gradually worse each year. By 2013-14, the Dons bottomed out, connecting at a 64.8 percent clip, the worst in the WCC and a lowly 327th (out of 351 teams) in the NCAA; USF was averaging between eight and nine missed freebies per game. Yet, somehow, the Dons managed a 21-12/13-5 record that year, missing out on the NCAA tourney but receiving an invite to the NIT.

That was the Walters era in a nutshell: a maddening inconsistency guaranteed to inflame the stomach lining (not to mention the incessant tinnitus). In the aftermath of the Jessie Evans dilemma, with the coach taking a leave of absence in 2007 (assuming he would be given the job back, Evans subsequently filed a wrongful-termination lawsuit against the department), the USF basketball program was in dire shape. The team wasn’t winning, the crowds were infinitesimal (except when Adam Morrison and Gonzaga visited War Memorial and the building was above capacity, with people streaming in off the street through the unlocked upper entrances well after tipoff14) and were on the verge of sanctions if the quality on the court and the number of asses in the seats did not improve. With the seventy-one-year-old, once-retired Eddie Sutton not a long-term prospect, USF needed someone fairly well-known but not so long in the tooth.

Walters, thirty-eight, fit both bills. An outstanding shooter, Walters was recruited by USF, at the time coached by Jim Brovelli, but he opted to sign with Northwestern, where he played for two years before transferring to Kansas to play two more. Walters could score from anywhere, finishing his college career a 50 percent shooter, including 42.6 percent from beyond the arc. His 1992-93 Kansas team reached the Final Four, falling to eventual national champion North Carolina. The New Jersey Nets selected the undersized Walters in the first round, and he would go on to play seven seasons in the NBA primarily as a role player off the bench. Walters began his coaching life in 2003 as an assistant at Valparaiso, then as an assistant at Florida Atlantic, eventually taking the reins there in 2006. After two unremarkable seasons leading the Owls, Walters found himself on the Hilltop giving his opening press conference, speaking of banners and academic success. Brovelli was on the search committee. “I lost the battle but won the war,” he quipped. “I got him to sign a letter of national intent 20 years later.”

Rex Walters lasted eight years on the Hilltop, the longest tenure since Phil Mathews’s nine-year stint. Although the Dons made a few postseason appearances – the CollegeInsider.com Postseason Tournament (CIT) in March 2011, the College Basketball Invitational (CBI) in March 2012, and the National Invitational Tournament (NIT)15 in March 2014, the Rex Walters Dons were inconsistent from year to year, floating between bad and good and mediocre, especially in conference play.

The unforgiving aural assault of ball hitting rim as Cole Dickerson or Kruize Pinkins or Matt Glover or Mark Tollefson clanged the front-end of one-and-ones certainly played a role in the Dons’ maddening fluctuations, since leaving points at the line can effectively swing close games, and opponents become unafraid to play physically and risk fouling.

BUT THAT WAS ONLY WHAT you read in the box scores or saw play out from the seats. What happened behind the scenes ultimately sealed Walters’s fate.

It was during a practice session at War Memorial Gym on November 19, 2013, when tempers flared between two players, senior guard Cody Doolin and sophomore (and fellow guard) Tim Derksen. According to a witness, Walters then told Doolin and Derksen, “You can either practice, or you can fight” before arranging the team in a circle. The two combatants traded blows inside the circle for thirty seconds before they were pulled apart. Neither player was hurt, but Doolin was sufficiently shaken by the event that three days later he quit the team and went back home to Texas. He later transferred to UNLV. (Dirksen stayed on and graduated from USF in 2016.)

Doolin was the twenty-first player to depart with NCAA eligibility remaining since Walters took over. Eleven players – all Walters recruits – had left in a 23-month span, including six after the 2011-2012 season ended.

“I don’t understand the reason [Walters] is still in place,” a former USF assistant, speaking on condition of anonymity, told the San Jose Mercury News, considering how Rutgers head coach Mike Rice had recently been deposed after a video of him physically and verbally abusing his players went viral on the Internet. For their part, the players who departed the Hilltop were diplomatic in their assessments of their former coach but made it clear that Walters made them uncomfortable.

Michael Williams, who transferred to Fullerton: “Coach Rex always has his game face on. You feel like you have to be serious all the time. That’s what players wanted to get away from.” And, “I just couldn’t play for him.” Williams also pointed to the constant churn of assistant coaches. “You could tell by how the locker room was. It was no longer a unit.” The lack of continuity among the coaches may have fed into the Doolin-Derksen fracas. “Something like that would have never happened when we were there,” an unnamed former assistant said. “We would have said, ‘Coach, this is not a good idea [allowing the two players to fight].’ With the young guys there, they let it happen.”

Perris Blackwell, after moving to the University of Washington: “There’s nothing wrong with being intense, but I felt like he rubbed people the wrong way. It was too hostile all the time. It didn’t feel like home when we were practicing, and some people were really uncomfortable.” Blackwell, a forward, played one season for Lorenzo Romar’s Huskies and started all but the final six games. He graduated U-Dub in 2014 with a degree in communications.

Justin Raffington, who departed for Rex Walters’s former place of employment, Florida Atlantic: “The formula has been [to] put the players on a chopping block. Can we get someone who appears to be better than what we have? That’s with coaches and players. And you get into this spiral where you get 21 transfers.” An undersized center who seldom played at USF, the German-born Raffington started for most of his two seasons in Boca Raton, graduating in 2015 with degrees in marketing and international business.

De’End Parker, who transferred in from UCLA, played one year for Walters and saw his playing time dwindle, recalled that he and the coach “did not see eye to eye.” Parker was dismissed in May 2013 “due to conduct detrimental to the program.” Parker transferred to Cal State San Marcos, a National Association of Intercollegiate Athletics (NAIA) school, due to having no more eligibility at the NCAA level.

“Rex is a nice guy,” said another former assistant. “He does a lot for people. But Rex can be tough to deal with.”

On March 9, 2016, USF fired Rex Walters with two years still remaining on a contract extension he signed in 2011.

The young, splashy hire who was supposed to rescue USF men’s basketball from the torpor of the Jessie Evans era left the Hilltop with a pedestrian 127-127 overall record, including 63-65 within the WCC and 2-3 in low-level postseason tournaments, with a number of players setting land speed records for getting the hell out of there.

There were no new banners hung.

The Golden Era and the Way Forward

IF IT SEEMED TO YOU like Kyle Smith and Todd Golden were joined at the hip, you would be forgiven. Such light canon may not be entirely true, but sometimes perception is reality.

Golden played point guard at St. Mary’s from 2004-2008, during which the Gaels went to a pair of NCAA Tournaments and were frequently nipping on Gonzaga’s heels in the battle for WCC supremacy (although Loyola Marymount and Santa Clara were able to get a word in). Kyle Smith was one of head coach Randy Bennett’s assistants at the time, having been hired in 2001. Bennett took over a Gaels basketball team that was deep down in the doldrums’ doldrums, one that had finished the 2000-01 season under Dave Bollwinkel 2-27/0-14. Bollwinkel resigned after that season and Bennett, who was Lorenzo Romar’s assistant at Saint Louis, was hired. He brought along Smith – the two had worked together under Brad Holland at the University of San Diego in the mid-1990s – and the two began transforming the program at warp speed. In Bennett’s third season – Golden’s freshman year – St. Mary’s posted a 25-9/11-3 record and made their first NCAA tourney since the Ernie Kent-coached Brad Millard-David Sivulich-A.J. Rollins 1996-97 squad. A deep reserve as a freshman, buried behind senior guards Paul Marigny, E.J. Rowland, and Jonathan Sanders, Golden would see his playing time jump as a sophomore, starting 28 of 29 games, dropping in 194 points while dishing out 94 assists, but also turning the ball over an unacceptable 46 times. Golden’s ball-handling improved with experience, and as a senior in 2007-2008 he finished second in the NCAA with an astounding 3.6-to-1 assist-to-turnover ratio.

Because he was not a prolific scorer, Golden went untouched in the 2008 NBA draft. A dual U.S.-Israeli citizen of Jewish faith, Golden instead ventured to Haifa, Israel’s third-largest city, where he would play two seasons with Maccabi Haifa B.C. Then, after a couple of years working in advertising, he got his first coaching gig when his St. Mary’s, mentor, Smith, asked him to join his staff at Columbia University, where Smith had taken over in 2010. In 2014, when Smith was hired to replace Rex Walters on the Hilltop, he brought his twenty-nine-year-old protégé with him.

JUST AS WALTERS WAS TASKED in 2008 with rescuing the program from the somnambulism of the Jessie Evans years, Kyle Smith was handed the duty of delivering the USF Dons from the tumult of Walters’s stint. The main objectives were to, of course, become a regular presence in the top-half of the WCC table, but also recruit and retain talent, a crucial skill needed to compete with the likes of Gonzaga, who made reloading their rosters seem effortless. Smith inherited a young squad; he had only one junior, Chase Foster, and a lone senior in Ronnie Boyce. He also had a redshirt sophomore, point guard Frankie Ferrari, who was returning to the Hilltop after spending his true sophomore season at Cañada College in suburban Redwood City. Then, there was a quartet of freshmen whom Smith had recruited to be the future of the program: guards Charles Minlend Jr. and Jordan Ratinho; forward Remu Raitanen, out of the Helsinki Basketball Academy in Finland; and massive seven-foot center James “Jimbo” Lull.

Under Smith, the Dons would showcase an uptempo style of offense and volume shooting (especially from beyond the arc), an analytically driven approach, while plucking elements from the so-called “Princeton offense,” a notoriously slow, constant-motion style popularized by Princeton coach Pete Carril in the 1970s, which made extensive use of screens and backdoor cuts into the paint16. Another benefit of the Princeton offense is that it doesn’t require a skilled point guard, since all five players on the floor are required to master passing, dribbling, outside shooting, and post-play inside. Smith could feel free to deploy a pair of shooting guards at the same time if he chose.

Kyle Smith would lead the Dons for three seasons, and although the results could be viewed as mixed, there was no doubt that the program was at least heading in the right direction. Smith became the first coach to win 20 games in his first three seasons, winning 63 total. Each team also won either nine or ten games within conference. But in all three years, USF finished fourth in the WCC behind Gonzaga, St. Mary’s, and Brigham Young17. The first two teams gained entry into the College Basketball Invitational (CBI). The 2016-17 team fell to Rice in the first round; the 2017-18 team dispatched Colgate, Utah Valley, and Campbell before dropping a best-of-three championship series to North Texas. After a 21-win 2018-19 campaign, Smith had hoped for a bid in the National Invitational Tournament (NIT), but the Dons were ignored. “The disappointment of not getting an invitation to the NIT is a testament to how far the program has come so quickly,” Smith said afterward. USF announced it would decline any invitation to a lower tournament.

Nine days later, Kyle Smith was gone, having accepted a head coaching job with the Washington State Cougars. The void would be filled by his former player, protégé, and top assistant. At age thirty-four, Todd Golden’s time had come.

ALTHOUGH GOLDEN’S ASCENSION MAY NOT have been a surprise – he seemed ticketed for a top job sooner or later – Smith’s departure was. Short of a retirement, in which the coach receives a gold watch, a bouquet of flowers, and a lifetime membership to the local country club, a typical departure is usually on less-than-ideal terms: a string of bad seasons, poor academic performances from the student-athletes, cheating scandals, and so on. But Washington State had just fired its coach, sixty-four-year-old Ernie Kent, and was looking for someone younger but with a tangible track record. The Cougars got an assist from Klay Thompson, a former WSU standout who had become a Bay Area basketball legend as a member of the Golden State Warriors, winners of the three of the last four NBA Finals. “Every program he’s been at he’s turned around,” Thompson said. “I think he’d be a great get.”

USF would not suffer any drop-off as a result of the coaching change. Golden was well-versed in analytics and in the Princeton offense, having first learned them under Smith when they were together at Columbia. In time, the Dons would become better defensively, culminating in a 95.2 rating in 2021-22 that ranked 50th out of 358 teams. But if alums, fans, and donors alike hoped Golden would be a longtime fixture on the Hilltop, those hopes were dashed after the Dons’ first NCAA Tournament in twenty-four years wrapped up with the first-round loss to Murray State on March 17, 2022. Like his mentor Smith, Golden would lead the Dons for just three seasons, then make the jump to a major conference when he agreed to a six-year deal to lead the Florida Gators of the Southeastern Conference (SEC).

Golden would be replaced by Chris Gerlufsen, ten years Golden’s senior, who had been Golden’s associate head coach and ran the team’s offense. He possessed a modicum of head-coaching experience, having served thirteen games as an interim at Hawaii back in 2019. Coming on the heels of Kyle Smith’s and Todd Golden’s successes in reinvigorating the program, Gerlufsen had massive shoes to fill.

Conclusion

IT’S NOT INFELICITOUS TO CHARACTERIZE the reconstituted USF men’s basketball as having been less than successful; after all, in the thirty-seven completed seasons (2022-23 will be the 38th) since the program’s 1985 rebirth, the Dons have reached the NCAA Tournament just twice. In the final ten years before their voluntary shutdown in July 1982, USF basketball made the big dance seven times.

The college basketball landscape has changed greatly in the years since. In ‘85, there were 283 teams competing in the NCAA's uppermost tier. Today, there are 363. Games are on television more now than ever, Internet discourse ensures that every decision will be scrutinized ad nauseam, and the new Name, Image, and Likeness (NIL) policy ensures that student-athletes get to earn some cash for their efforts on the court, field, diamond, or pitch — efforts that generate the revenues needed to fulfill the million-dollar contracts that a lot of coaches receive18.

The importance of recruiting has not changed. It’s the foundation of any successful college sports program. But recruiting is an inexact science, which heightens the importance of coaching – specifically, the ability to quickly diagnose players’ strengths and flaws and customize their instructions accordingly. A basketball player with immense ability can be rendered inert and impotent if his coaches don’t know how to properly use him; one with modest ability can emerge as a key contributor if put into positions to maximize that ability.

Gonzaga does this well. On the surface, their style of offense seems antediluvian, as they’ve largely eschewed the current trend of turning each basketball game into a 3-point-shooting contest. Mark Few, the Zags’ sandy-haired, grizzled head coach of nearly a quarter century, has been wildly successful with this inside-out style of offense, in which his players probe the paint looking for easy shots (and often making them), while also not shying away from contact and frequently drawing enough fouls to quickly enter the bonus. They occasionally pop from distance, just to keep their opponent honest. Few and his staff recruit players to fit this style: players who are big and physical, but also skilled (the Zags’ forwards and centers must be able to pass, or else be glued to the bench). Gonzaga struggles against bigger, quicker teams – their 2021 NCAA Finals loss to Baylor and its stingy defense highlights this – as well as a number of early-round losses – but their system works nearly to perfection against most everyone else.

MARK FEW HAS BEEN AT his post since 1999. In that same time frame, the USF Dons have employed five head coaches (not counting Eddie Sutton’s cameo). Continuity is fertile ground for recruiting. Frequent turnover of coaches often puts players in a position of having to learn and adopt a new philosophy and absorbing directions from someone they have no personal connection to (coaches often visit recruits’ homes and meet their families). Such churn also engenders the illusion of instability. Who can be certain that the guy trying to lure you to his program will even be around in two years? The Dons presently occupy an odd space: They lack the track record of success that Gonzaga and St. Mary’s have amassed, yet, in recent years they have done well by more modest USF standards. But they had two coaches in a four-year period leave to take jobs in major conferences: Kyle Smith, to the Pac-12; Todd Golden, to the SEC. If Chris Gerlufsen is successful at USF, can we be assured he won’t be lured away by the prestige and paycheck of, say, the Big Ten or Big 12? Is the Hilltop destined to be little more than a launchpad for aspiring young coaches?

At age forty-six, Gerlufsen may not be the up-and-coming prospect that the younger Golden was, so his future on the Hilltop could very well be secure, as long as he is successful. But he is also older than what Few and Bennett were when they took over their posts back in 1999 and 2001, respectively, so time may not be as much on his side. Nonetheless, he has the opportunity and the resources, not to mention his past experiences as Todd Golden’s lead assistant, to put together and develop a winning roster that will compete with the likes of Gonzaga and St. Mary’s while becoming at least a semi-regular presence in the NCAA Tournament and sending an occasional player or three to the NBA19, just like in the good old pre-Death Penalty days.

Sources:

Adams, Bruce. “Coach Mathews Fired By USF.” San Francisco Chronicle, March 9, 2004, pg. C1.

Adams, Bruce. “Mathews: ‘I Didn’t See It Coming.” San Francisco Chronicle, March 11, 2004, pg. D4.

Adams, Bruce. “USF Finds the Man It Wants – Evans to be Dons’ Coach.” San Francisco Chronicle, April 21, 2004, pg. D1.

Barry v. Time, Inc., 584 F. Supp. 1110 (N.D. Cal. 1984). Justia.com. https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/584/1110/2270300/

Becker, Jon. “USF’s Basketball Team Decides Not to Play in Tournament.” San Jose Mercury News, March 18, 2019. https://www.mercurynews.com/2019/03/18/usfs-basketball-team-decides-not-to-play-in-tournament/

Boyle, Robert H. “Bringing Down the Curtain.” Sports Illustrated/Vault.SI.com, August 9, 1982. https://vault.si.com/vault/1982/08/09/bringing-down-the-curtain

Carroll, Gerry. “Emotions Reign as Dons Stun Irish.” San Francisco Examiner. January 8, 1989, pp. C1, C5.

Chu, Bryan. “USF Hires Rex Walters.” San Francisco Chronicle/SFGate.com. April 15, 2008. https://www.sfgate.com/sports/article/USF-Hires-Rex-Walters-3287292.php

Crumpacker, John. “Ex-Dons Adjust to New Lives.” San Francisco Examiner. December 19, 1992, pp. C5-C6.

Curiel, Jonathan. “USF Chooses A Hard Worker – Mathews Succeed Brovelli.” San Francisco Chronicle. July 12, 1995, pg. D1.

Curtis, Jake. “USF Shocker: Brovelli Quits as Coach.” San Francisco Chronicle. May 8, 1995, pp. D1, D6.

Curtis, Jake. “USF Talks to Purdue’s Kelly.” San Francisco Chronicle. March 26, 2004, pg. D3.

Curtis, Jake. “Struggling USF Turns to New Mentor.” San Francisco Chronicle. December 27, 2007, pg. D1.

Curtis, Jake. “De’End Parker’s career revived at Cal State San Marcos.” San Francisco Chronicle/SFGate.com. February 18, 2014. https://www.sfgate.com/collegesports/article/De-End-Parker-s-career-revived-at-Cal-State-San-5246399.php

“Dante Benedetti (1972)” - https://usfdons.com/honors/hall-of-fame/dante-benedetti/200

D’Hippolito, Joseph. “Big USF Rally Lifts Sutton to 800.” San Francisco Chronicle. February 3, 2008, pg. D5.

“Dons Rally From 19 Down to Hand Sutton No. 800.” ESPN.com. February 3, 2008. https://www.espn.com/mens-college-basketball/recap?gameId=280332492

Dubow, Josh. “Kyle Smith Hired As Washington State Coach.” Associated Press. March 27, 2019. https://apnews.com/article/0d6f260c31814b01b0322d4ec35e3433

Faraudo, Jeff. “Is University of San Francisco’s Successful Hoops Season Masking Other Issues?” San Jose Mercury News/MercuryNews.com. March 1, 2014. https://www.mercurynews.com/2014/03/01/is-university-of-san-franciscos-successful-hoops-season-masking-other-issues/

FitzGerald, Tom. “Gervais Out; 49er Secondary Reeling.” San Francisco Chronicle, October 4, 1983, pg. 46.

FitzGerald, Tom. “USF: Evans lost control.” San Francisco Chronicle, March 11, 2008. https://www.sfgate.com/sports/article/USF-Evans-lost-control-3291828.php

“Former University of San Francisco basketball coach Peter Barry...” UPI Online Archives, August 22, 1983. https://www.upi.com/Archives/1983/08/22/Former-University-of-San-Francisco-basketball-coach-Peter-Barry/8727430372800/

“Grateful Web Interview With Michael Franti” - https://www.gratefulweb.com/articles/grateful-web-interview-michael-franti

Isaacson, Melissa. “Dailey's legacy More Than Controversy.” ESPN.com, November 15, 2010. https://www.espn.com/chicago/nba/columns/story?columnist=isaacson_melissa&id=5810529

Jupiter, Harry. “Quintin Dailey, USF Sued by Woman He Assaulted,” San Francisco Chronicle. October 13, 1982, pg. 2.

Kroner, Steve. “Rex Walters Out As USF basketball Coach.” San Francisco Chronicle/SFGate.com. March 9, 2016. https://www.sfgate.com/collegesports/article/Rex-Walters-out-as-USF-basketball-coach-6879872.php

Littwin, Mike. “THE DONS ARE BACK: Jim Brovelli, the Coach, Is Faced With Building a Program That Maintains Tradition of Winning While Ending Tradition of Cheating to Win,” Los Angeles Times, March 10, 1985. https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1985-03-10-sp-25904-story.html

Martin, Douglas. “Quintin Dailey, Gifted but Troubled Player, Dies at 49.” New York Times. November 10, 2010, https://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/11/sports/ncaabasketball/11dailey.html

McGrath, Dan. “A USF ‘Victim’ on the Road to Recovery,” San Francisco Chronicle. December 27, 1984, pg. 47.

Miller, Ira. “Brovelli’s Plan: Patience,” San Francisco Chronicle. April 6, 1984, pp. 75, 82.

Nevius, C.W. “USF Could Win Again If It Supports Its Coach,” San Francisco Chronicle. May 9, 1995, pg. D1.

Rogers, Thomas. “Scouting,” New York Times (archived). October 11, 1984, https://www.nytimes.com/1984/10/11/sports/scouting-003391.html

Sullivan, Pat. “The Uproar Over USF’s Athletic Program,” San Francisco Chronicle. November 29, 1983, pg. 7.

Thomas, Ron. “Bulls Deny Dailey’s ‘Unfairness’ Claim,” San Francisco Chronicle. January 30, 1985, pg. 59.

“USF alum ‘Says Hey’ — from Bali” – SF Foghorn http://sffoghorn.com/usf-alum-says-hey-from-bali/

“USF Roster At Five After Three Signings,” San Francisco Chronicle. November 15, 1984, pg. 72.

“USF to Name Brovelli Coach,” San Francisco Chronicle. April 5, 1984, pg. 71.

Barry v. Time, Inc., 584 F. Supp. 1110 (N.D. Cal. 1984). Read it here: https://law.justia.com/cases/federal/district-courts/FSupp/584/1110/2270300/

The New Pisa closed in 2003. The original location, from 1920 to 1977, was at 1268 Grant Avenue.

The Pacific Coast Athletic Conference became the Big West Conference in 1988.

Players generally weren’t allowed to be drafted until their senior years, but Dailey successfully applied for a hardship waiver to enter the 1982 NBA draft.

Hank Gathers tragically passed away on March 4, 1990, hours after collapsing in a WCC Tournament game against the Portland Pilots at LMU’s Gersten Pavilion. He had previously been diagnosed with an irregular heartbeat.

The West Coast Athletic Conference (WCAC) became the West Coast Conference (WCC) in 1989.

An epileptic, Cross died in his Redmond, Washington, home in 1977 following a seizure. He was just twenty-eight years old.

The Sobrato family has graciously donated countless millions of dollars for various USF causes. The Sobrato Club was funded by a $15 million grant from John and Susan Sobrato, the largest individual gift in school history. You can read about it here.

St. Joe’s fell off precipitously after 2005, posting double-digit win totals in-conference just three times over the ensuring fourteen seasons. Phil Martelli was axed in 2019 after the Hawks finished 14-19/6-12. He had served at the school since 1985, beginning as an assistant under Jim Boyle.

Kentucky infractions were numerous. One player was suspected of cheating on an entrance exam and voluntarily sat out until the investigation was complete. A cash sum of $1,000 was discovered in an envelope an assistant coach supposedly sent to the father of another player (the coach was later cleared of wrongdoing). Boosters were found to have slipped student-athletes cash, and free meals and other perks were dished out. Kentucky was hit with a three-year probation, sparing themselves the death penalty by cooperating with the investigation.

The Big 8 became the Big 12 in 1996, when the conference added Baylor, Texas, Texas A&M, and Texas Tech in the aftermath of the Southwest Conference’s dissolution.

Sutton’s blood-alcohol level was .22, three times the legal limit.

I remember this well, as it was the first USF basketball game I ever attended. I sat in upper bleachers behind the baseline, in the second row, and near the corner.

The Dons’ first national championship in 1949 was via the NIT, which was the premier postseason tournament at the time. The NCAA Tournament usurped the NIT in the early 1950s.

If recall from earlier in this piece, it was Carril and the Princeton Tigers who defeated Jim Brovelli’s San Diego Toreros in the 1984 NCAA Tournament, mere weeks before USF hired him to help restart the program.

BYU joined the WCC in 2011 after 12 years in the Mountain West; and, before that, 37 in the Western Athletic Conference (WAC).

In many cases, football coaches are the highest-paid state employees. Examples include Alabama’s Nick Saban, USC’s Lincoln Riley, Jim Harbaugh of Michigan, and Mack Brown at North Carolina. Basketball coach John Calipari is the highest-paid state employee in Kentucky.

Jamaree Bouyea, an undrafted free agent, recently made his NBA debut with the Miami Heat, becoming the first USF Don to reach the highest level of pro basketball since Ime Udoka, joined the Lakers in 2004. Udoka played one year on the Hilltop and a year at Portland State; undrafted, he bounced between various overseas and developmental basketball teams for several years before latching on in Los Angeles. He played his final NBA game in 2011, as a member of the San Antonio Spurs, with whom he would later win a title with as an assistant coach.