Tracing the Role of MLB's Commissioner

The job of Major League Baseball's commissioner is to be a steadfast and obdurate lapdog for the league's thirty owners. But that wasn't always the case.

Note: I started writing this several days ago during the height of the owner-instituted lockout. Now it looks like there’s an agreement in place and we will have a season, even if slightly delayed.

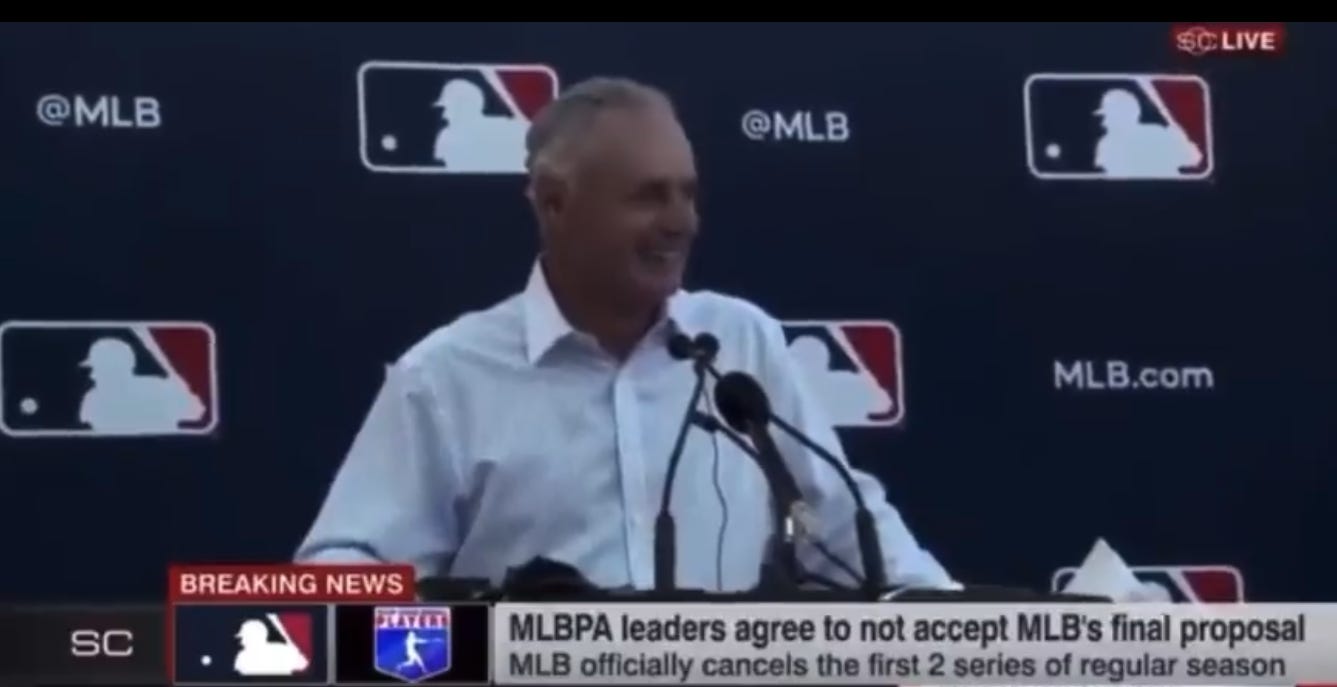

Giggling and grinning like a Cheshire cat that had just gotten laid, MLB commissioner Rob Manfred announced on March 1 that the first two series of the upcoming season would be cancelled (more recently expanded to the first two weeks, before an agreement was finally reached). At the rate things are going, by the end of this month ol’ tennis ball head will be rolling on the floor in wind-sucking hysterics, like a baby being tickled, as he announces that the first game of the season will be the All-Star Game.

But, honestly, being mad at Manfred is a feckless exercise. It was the owners who created this jam, and the commissioner is just the front man. He is the owner’s obedient lap dog, tasked with delivering the messages they themselves don’t want to deliver, while he takes the blows from an exasperated and bemused public. As the saying goes: “don’t hate the player, hate the game.” Pretty much all of baseball’s problems are deeply entrenched and systemic. This will come as a cold slap in the face to the “Manfred must step down” crowd, but he’s just a highly decorated pawn in this fucked-up chess game. Rob Manfred magically going away won’t fix a single thing; the owners will simply adopt another lap dog from the Commissioner Kennel and nothing will change. Same goes for if Manfred pulls a Bart Giamatti and dies while in office. (More on Giamatti later.)

However, the commissionership of baseball wasn’t always like this. The first dominoes that fell that brought us to this point — in which baseball’s owners have nearly unfettered and unchecked power — took place roughly forty years ago. Before that, the game’s top steward wasn’t beholden solely to the owners, even though he was hired by, and served at the pleasure of, the owners. The commissioner’s job was to look out for the industry’s best interests.

The roots of MLB’s commissioner post

In 1919, several members of the Chicago White Sox conspired to purposely lose the World Series to the underdog Cincinnati Reds, at the best of a gambler named Joseph “Sport” Sullivan. Gamblers like Sullivan had long been a part of the sport’s landscape, but when he met with Sox player Chick Gandil about the possibly of rigging a whole entire World Series, it broke new ground. For his part, Gandil wasn’t sure it would work, but he nonetheless sought and received assurances from some teammates, including Eddie Cicotte, Happy Felsch, and Lefty Williams, that they would play less than their best, cough up the Series, and collect roughly $100,000 total1.

At one point, the Series stood at 4-1 in favor of the Reds (the Fall Classic was a best-of-nine from 1919-1921), but the consortium of gamblers that Sullivan had cobbled together was failing to provide the payouts after each loss, as promised. The players involved in the fix called it off and the Sox won the next two games, and soon threats were being levied at the players and their families. Chicago dropped Game 8 to hand the Series to the Reds.

The results of 1919 Series went largely ignored, until evidence of a fix in a regular season game between the Chicago Cubs and Philadelphia Phillies emerged, thus casting a bright, pulsating Klieg light on the presence of gamblers in baseball. Soon, attention turned to the Sox-Reds series, one of the gamblers stepped forward, and Cicotte tearfully testified before a grand jury of his involvement. In October 2020, eight players were indicted. Dubbed the “Black Sox” scandal, it was a huge black eye for baseball at the time, despite the fact that the players were later acquitted after paper records of their court testimonies mysteriously disappeared.

Their relief wouldn’t last long.

Major League Baseball had been governed by a three-man National Commission, but by 1919 the owners were warming up to the idea of a sole commissioner to oversee the sport. Ideally, someone who would be a strong leader.

That someone was Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis, a man named after a major Civil War battle that his father had been wounded in. President Teddy Roosevelt appointed Landis to the United States District Court for the Northern District of Illinois in 1905, and made a name for himself as someone unafraid to take on big businesses when he sued Standard Oil of Indiana for more than $29 million for giving out rebates on railroad freight tariffs, a federal offense. His case was reversed on appeal, but it did not matter.

Kenesaw Mountain Landis had caught the eyes of the Lords of Baseball.

Installed as MLB’s first commissioner, Landis’s role was to act in the interests of baseball - a key phrase here: in the interests of baseball - and to do so with an iron hand, if necessary. Landis ruled the sport until his death in 1944, and was credited with cleaning up the game by cracking down on gambling. He also lifted a ban on major league teams owning minor league teams, paving the way for Branch Rickey to create and implement the modern player-development system.

After Landis’s death, he was replaced by Albert “Happy” Chandler, a former governor and senator from Kentucky. It was under Chandler that baseball finally became integrated, with his approval of Jackie Robinson’s contract with the Dodgers. He also instituted baseball’s first pension fund, which made the players extremely happy but pissed off the owners. They declined to renew Chandler’s contract, and he was out after serving less than six years.

Ford Frick, expansion, and inaction

Having served seventeen years as president of the National League, Frick was tabbed to succeed Chandler as Major League Baseball’s third commissioner. During Frick’s fifteen years at the helm, he oversaw a round of expansion that saw MLB swell from sixteen to twenty teams. He also took All Star Game voting away from the fans after a an organized ballot box-stuffing campaign was unveiled, in which most of the ballots came from Cincinnati and stacked the 1957 National League roster with Reds players. Frick kicked two of the Reds off the team and replaced them with players from other teams.

Besides that, Frick’s tenure was a big nothing. Whenever disputes arose, he refused to take action, often saying it was “a league matter.” Wrote Jerome Holtzman of the Chicago Tribune, “In retrospect, he understood his role. He was a caretaker, not a czar.”2 The idea of an MLB commissioner fitting Holtzman’s description seems so out of place today.

Upon Frick’s 1965 retirement, he was replaced by William “Spike” Eckert, a former Air Force general. Nobody knew who the hell he was, and at the time of his appointment to the sport’s highest office, he had not seen a game live in a decade. Although he succeeded in bringing international attention to Major League Baseball, specifically in Japan, where the Dodgers and, later, other teams, would hold exhibition games.

Eckert served only three seasons, and there were several factors in his undoing. He refused to postpone games in the wake of the Robert Kennedy and Martin Luther King Jr. assassinations3, a myopic decision that rankled the public. He then incurred the ire of the owners by failing to tackle business issues, and by 1968, anticipating a players strike (which didn’t happen, though there was a spring training boycott the following year), the owners had lost confidence in Eckert and forced him to resign.

Bowie Kuhn’s eventful tenure, and the rise of Marvin Miller

The 1960s saw two men take the reins in Major League Baseball and oversee a tumultuous and transformative time in the sports history. In 1969, Bowie Kuhn replaced Spike Eckert as commissioner. Three years earlier, Marvin Miller, the former lead negotiator of the United Steelworkers union, was elected to lead the brand-new Major League Baseball Players Association (MLBPA). Under Kuhn, who served until 1984, Major League Baseball added six new teams and instituted nighttime World Series games, but Kuhn also had frequent run-ins with owners, particular Oakland’s Charlie Finley, who forced one of his players, Mike Andrews, so sign a false medical document that would disable him for the rest of the 1973 World Series. Kuhn also nullified Finley’s attempt sell three of his players for a total of $3.5 million in 1976, claiming that the transactions were not in the game’s best interests, since it would leave the A’s with a badly depleted roster. He also engendered no love from Ted Turner, who was hit with tampering charges after he had made remarks about acquiring a player during a period when Kuhn had ordered owners to keep mum about their intents to sign free agents. Kuhn fined and suspended Turner, and docked the Braves a draft choice. “I’m thankful he didn’t order me shot,” Turner cracked.

Major League Baseball in the 1970s represented a sea change in how the game was run. In October 1969, when the Cardinals traded Curt Flood to the Phillies as part of a seven-player deal (Tim McCarver and Dick Allen were also involved), Flood refused to report, citing the Phillies bad record and racially abusive fans, and asked Kuhn to make him a free agent. When Kuhn refused, citing the reserve clause, in January 1970 Flood filed a lawsuit, which went all the way to the Supreme Court. Using the 1922 antitrust exemption granted to baseball, in March 1972 the high court sided with MLB, 5-3-1. The player was defeated; the reserve clause, which bound player to team in perpetuity, was left intact, but the die had been cast.

Enter Miller.

The former steelworkers’ negotiator would be a bane to baseball owners’ existence from the moment he took over the nascent MLBPA in 1966. He negotiated a huge pay increase for the players in 1968, and in 1973, instituted a new salary arbitration process in which cases went before neutral arbitration panels, rather than the commissioner. The Flood v. Kuhn case, would pave the way for the abolition of the reserve clause and the implementation of free agency in 19754. Players continued to make gains, thanks to Miller, as the 1970s rolled on, including an increase in pension fund payments. From 1966 through 1982, the average salary rose from $19,000 to $241,000. As the New York Times put it in their 2012 obituary, “If Mr. Miller had one overarching achievement, it was to persuade professional athletes to cast aside the paternalism of the owners and to emerge as economic forces in their own right, often armed with immense bargaining power. The changes he wrought in baseball rippled through all of pro sports, and it could be said that he, more than anyone else, was responsible for the professional athlete of today, a kind of pop culture star able to command astronomical salaries and move from one team to another.”5

The 1980s: Ueberroth, “Damned dumb,” and collusion

Things that were all the rage in the Eighties: big hair, neon clothing, spandex, leg warmers, acid-washed jeans, selling weapons to Iran, E.T., overly produced electronic music, Reaganomics, yoyos, Back to the Future, slap bracelets, Mikhail Gorbachev’s port-wine stain birthmark, and Major League Baseball owners colluding to keep salaries down.

As much as I’d like to dive into the sordid details of the American government’s sales of anti-aircraft and surface-to-surface missiles to Ayatollah Khomeini, or why Reagan’s supply-side economics were an unquestioned failure6 , the devious machinations of the Lords of Baseball in their quest to regain power weave a tale that, as far as sports fans are concerned, rival the development of the Gipper’s ham-fisted economic policy or Oliver North and company violating the Boland Amendment.

(Also, I’d do a pretty piss-poor job at explaining the other two things adequately without inadvertently glossing over shit.)

Bowie Kuhn and Marvin Miller stepped aside within two years of each other: Miller retired from running the MLBPA in 1982, and Kuhn, hounded by the 1981 strike, was forced out after the 1984 season when the owners refused to renew his contract. Kuhn was replaced by Peter Ueberroth, a Los Angeles businessman who had successfully led the charge to bring the 1984 Summer Olympic games to Tinseltown. But it was Miller’s departure, more than Ueberroth’s appointment, that gave baseball’s owners great relief. After sustaining so many wounds at the hands of Miller and the union during the 1970s, the owners must’ve felt great relief wash over them when the powerful MLBPA head stepped away.

The turning point happened in Ueberroth’s first meeting with the owners in 1985.

If I sat each one of you down in front of a red button and a black button and I

said, “Push the red button and you’d win the World Series but lose $10 million.

Push the black button and you would have a $4 million profit and you’d finish in

the middle.” You are so damned dumb. Most of you would push the red button.

Look in the mirror and go out and spend big if you want, don’t go out there

whining that someone made you do it.

With that confrontation, Major League Baseball was ushered into its first, and largest, era of collusion, a total of three years. During the 1985, 1986, and 1987 offseasons, the owners conspired to completely shut out free agents from signing contracts until the players lowered their demands. Players affected included Kirk Gibson, Carlton Fisk (who had a contract offer from the Yankees rescinded after White Sox owner Jerry Reinsdorf placed a call to George Steinbrenner), Jack Morris, Tim Raines, Andre Dawson, Ron Guidry, Bob Boone, Paul Molitor, and Jack Clark, among others. After each offseason, the MLBPA filed a grievance against MLB and the owners, who, spurred on by Ueberroth’s “damned dumb” speech, were finagling a way in which they could win and cut expenses, to get the best from pushing both the red and the black buttons.

In each case, a judge sided with the union. Several players were allowed into what was called “new look” free agency. Gibson, for one, used this to sign a three-year, $4.5 million deal with the Dodgers for the 1988 season. A final settlement was reached in late 1990, in which Major League Baseball agreed to pay the MLBPA $280 million in restitution.

By this point, Ueberroth was long gone, having stepped down in 1989. His successor, National League president A. Bartlett Giamatti, was supposed to be a pro-owner commissioner. As the president of Yale University from 1978 through 1986, Giamatti had dealt with labor unrest, having mediated a strike by the school’s clerical and technical workers in 1984-1985. That made him the top choice in the owners’ eyes; the fact that he was already in-house as National League president made the decision easier.

Unfortunately, Giamatti’s tenure as baseball commissioner was short-lived, as a heart attack took his life after just five months in office, a stressful five months in which he oversaw the Pete Rose gambling investigation that led to the longtime Cincinnati hero’s excommunication from the sport. Giamatti’s close friend and deputy, Fay Vincent, was next in the line of succession, and he wasted no time in becoming the owners’ bitter enemy. In 1990, shortly after taking over, he admonished his new bosses. “The single biggest reality you guys have to face up to is collusion,” he said. “You stole $280 million from the players, and the players are unified to a man around that issue, because you got caught and many of you are still involved.”7

No surprise, Vincent’s scathing commentary did not sit well with his bosses.

Fay’s ouster and Selig’s ascension

In September 1992, with the most recent Collective Bargaining Agreement a year away from expiring, and wanting a commissioner who would be squarely in their corner during negotiations for the new CBA, the owners did something unprecedented.

They took a vote of no confidence against Vincent. The tally was 18-9, with one abstention8.

“They voted no confidence because they didn’t have the balls to fire me because they knew I would beat them in court,” Vincent said years later. “I had a five-year agreement whose terms dates back to the first commissioner, Judge [Kenesaw Mountain] Landis. In essence, the contract says you cannot fire a commissioner during their term. I had hired Edward Bennett Williams and Brendan Sullivan to represent me and they assured me that I would win a case all the way to the Supreme Court, if necessary.”

Nonetheless, Vincent elected to step away on his own, because “I would have to work every day for people who don’t want me. Essentially, they didn’t like me because they wanted to break the union and I told them that wasn’t going to happen because of collusion and that I was firmly committed to building a better relationship with the union over a long period of time. They tried to break the union two years later in 1994 with replacement players and it backfired. They also didn’t like my realignment plans.” The language of Vincent’s resignation letter, dated September 7, 1992, portends the style of commissioner we would see in the twenty-first century.

Unfortunately, some want the Commissioner to put aside the responsibility to act in the “best interests of baseball”; some want the Commissioner to represent only owners, and to do their bidding in all matters. I haven't done that, and I could not do so, because I accepted the position believing the Commissioner has a higher duty and that sometimes decisions have to be made that are not in the interest of some owners.

—reprinted in the New York Times, 9/8/1992. [Emphasis mine.]

The heavy hitters behind Vincent’s ouster were a group of owners known as the Great Lakes Gang9. They included:

Allan H. “Bud” Selig (Brewers)

Jerry Reinsdorf (Chicago White Sox)

Stanton Cook (Chicago Cubs)

Carl Pohlad (Minnesota Twins)

And, even though they didn’t own teams in the Great Lakes regions, Bill Bartholomay of the Braves and Peter O’Malley of the Dodgers

With Vincent now out of the way, an interim would be named to fill the role. The Executive Council, comprised of eight owners, would be in charge. The Washington Post10 reported that former Eckert aid, Yankees general manager, and American League president Lee MacPhail was a possibility, but it was a foregone conclusion within the MLB fortress that the owners wanted to elevate Selig to the role of the Council’s chairman, thus enabling him to become the interim commissioner11.

In hindsight, it’s clear that Bud Selig was the man the other owners wanted helming the ship all along. Not only was Selig part of the Great Lakes Gang that pushed out Fay Vincent, but he — along with the White Sox’s Reinsdorf — were the biggest champions of the 1985-1987 collusion efforts, and he was the leading voice on behalf of baseball’s small-market teams, such as the Kansas City Royals, Cincinnati Reds, Pittsburgh Pirates, St. Louis Cardinals, Montreal Expos, Minnesota Twins, and Selig’s own Milwaukee Brewers. Now he was in charge, if only in title (MLB would still fall primarily under Council rule). The “interim” tag would last for an incredible six years, encompassing two aborted search committees and a nearly eight-month-long players' strike. On July 9, 1998, the thirty team owners unanimously elected Selig to a full-time role, making him the ninth commissioner in MLB history.

“I hear people say, ‘He’s an owner and he’s one of them,’” the newly minted commissioner said minutes after getting their imprimatur. “First and foremost, for those who know me, I am a fan. There is no one who could love this game more than I do — its history, its tradition, its honor and, above all, its decency.”12

Selig became the first owner to ever serve as MLB commissioner, and his elevation to the post would thrust baseball into an era of cynicism that continues to this day: the sport’s top leader would no longer, as in the past, be beholden to the best interests of baseball. The new role of the man occupying the office at 245 Park Avenue13 in New York City would be to ask “how high?” when his bosses told him to jump.

The Commissioner of MLB was, now, a lapdog.

A neutered lapdog.

Not that Bud pleased all the owners all the time. George Steinbrenner felt picked on when topics of a salary cap and luxury tax were brought up, and the Yankees’ boss never felt compunction about picking up the phone and hectoring Selig about them. Still, under Selig (including his “interim” time), Major League Baseball expanded into four new markets (Denver, Miami, Phoenix, Tampa Bay), and the sport rebounded nicely following the strike, thanks to an epic homerun chase between Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa in 1998 that was fueled by enough drugs to wipe out a Potemkin village. And, by the late 1990s, MLB had become a Potemkin village, because underneath all the homeruns and the cute commercials and the swift rebounds in attendance was another scandal bubbling the surface.

I won’t go too much into the details about PEDs here; that’s well beyond the scope of this piece. Long story short - Selig, and by extension, MLB, turned a blind eye to the rampant drug usage that infiltrated baseball. That’s because there was a tangible benefit to players blasting steroids into their veins: homerun totals skyrocketed, highlighted by Mark McGwire’s and Sammy Sosa’s twin assaults on Roger Maris’s single-season record in 1998, finishing with 70 and 66, respectively. Three years later, Barry Bonds, flashing a physique that looked like a lumpy mattress and an oversized head with bulging skull plates, passed both of them by, slugging 73 round-trippers. The sudden surge in homeruns was certainly good for business in years following the 1994-1995 strike; the longball displays helped erode fan apathy and enmity, as attendance jumped from just 25,021 patrons per game in 1995 to 29,030 in 1998 to a shade under 30,000 in 2001. Greater attendance equals more revenues, which means larger profit margins. Bud Selig owed it to his bosses to not say shit about PEDs. Though, to be fair, the MLBPA was very much against any form of drug testing (“I have no doubt that [steroids] are not worse than cigarettes,” Gene Orza, a union official, once said). It wasn’t until Ken Caminiti’s death in 2004, at age forty-one, from a heart attack, that baseball finally took notice. Caminiti had admitted his steroid usage after his playing days ended in 2001, was ostracized from the game, and spiraled in a life of alcoholism and drug abuse. Drug testing was implemented in 2006.

Selig gives way to Manfred

Baseball’s economic picture improved under Bud Selig’s stewardship, thanks to the explosion in television money14. But, during Selig’s tenure, there have been more collusion allegations, most notably in 2008 when the MLBPA accused the owners of conspiring to keep Barry Bonds out of baseball. There has been more speculation of collusion since Selig’s successor, Manfred, took the reins in January 2015 following Bud’s retirement; in particular, a preternaturally quiet 2017-2018 offseason. Since Manfred has taken over there has been the not-so-minor issue of service manipulation, in which young players are purposely held in the minors for the first couple weeks (or longer) before being promoted to the bigs for the first time15, thus delaying their arbitration and free-agency eligibility dates for a year.

That takes us to the CBA battle unfolding before us in early 2022. For years — especially recently — the owners have been unafraid to wield the power that they have gained, primarily by making the commissioner (first Selig, now Manfred) their own personal shill, to enact largely player- and fan-unfriendly measures. The whole point of this offseason’s charade, in which the owners locked out the players and refused to negotiate for well over a month thereafter, then setting do-or-die deadlines, throwing in last-minute topics to ponder (such as the international draft), is to break the union, something that Reinsdorf has been dying to do for the better part of the last three decades. Since Marvin Miller took over the nascent union back in 1966, it has remained largely strong, even though it has teetered at times. Still, through their commissioner, the owners maintain almost unfettered and unchecked power over the MLBPA, to the detriment of the labor, the consumers, and the industry at large. Whereas the owners’ best interests once were tied with the best interests of baseball, over the last thirty years that has flipped: the owners’ best interests are the in the best interests of the sport.

It should not be that way, but here we are.

Economic growth can be a good thing, up to a point, then you have to start thinking about the law of diminishing returns. That’s especially the case in baseball, where the values of baseball franchises of skyrocketed to an absurd degree, to the point where most, garden-variety millionaires can no longer acquire them, at least not as lead investors (they’re certainly free to buy in as small-time minority partners); only multi-billionaires are seen as being capitalized enough to gain acceptance into the owners’ coffee klatch. Way back in 1980, Walter A. Haas Jr. purchased the Oakland Athletics for a cool $12.7 million; if run that figure through an inflation calculator, it comes out to nearly $44 million in 2022 dollars. In contrast, when Jim Crane bought the then sans-trophy16 Houston Astros in 2011, he paid $680 million. Just a few months later, Frank McCourt sold the Los Angeles Dodgers to Guggenheim Baseball Management (Mark Walter, Stan Kasten, Peter Guber, Magic Johnson, et. al.) for $2 billion. Of course, compared to the Astros, the Dodgers are the older, more storied franchise with seven World Series titles, but the larger point stands: the game is now in the hands of people far more moneyed and powerful than it was when you or I were kids. And these are the types of people who - a.) care more about adding to their wealth than they do actual baseball, and b.) will seek to break the MLBPA if they feel the players are a threat to the first objective.

Conclusion

The silver lining here is that these 2022 negotiations could very well represent the owners’ best, and possibly last, punch. If the players’ union can hold steady and not settle for less than their asking price (obviously some concessions may be required — that’s the nature of it — but not to where they undermine their position), then, who knows? We could see a prolonged era of peace between the two sides.17 That would be in the best interest of baseball.

[Ed. note: the union’s executive subcommittee voted against the CBA 8-0, but the thirty team reps approved the deal 26-4. No idea what the ramifications will be, if any, for the player reps voting against the subcommittee.)

Roughly $1.6 million in 2022 dollars, factoring in a 1,525.1 percent cumulative rate of inflation.

Holtzman, Jerome. “To Survive, Fay Should Sit This One Out.” Chicago Tribune, July 26, 1992.

There was some precedent here. NFL commissioner Pete Rozelle famously declined to postpone games in the aftermath of the JFK assassination in Dallas in 1963.

The path to league-wide free agency received a giant nudge in 1974, when an arbiter ruled that Oakland A’s pitcher Jim “Catfish” Hunter was a free agent on grounds of a breach of contract; owner Charlie Finley had failed and refused to pay Hunter his annuity per the contract. Marvin Miller encouraged two other players, Andy Messersmith and Dave McNally, to play the 1975 season without a contract, then file for grievance arbitration. Both were awarded free agency, further eroding the power of the reserve clause.

Goldstein, Richard. “Marvin Miller, Union Leader Who Changed Baseball, Dies at 95.” New York Times, November 27, 2012; https://www.nytimes.com/2012/11/28/sports/baseball/marvin-miller-union-leader-who-changed-baseball-dies-at-95.html

Poor George Bush. His predecessor’s tax cuts left him with a historic budget deficit, and, dealing with a Democrat-controlled Congress, in 1990 Bush had no choice but to raise taxes, engendering some comedic mockery of his “read my lips, no new taxes” campaign line from August 1988.

Vincent, Fay, The Last Commissioner: A Baseball Valentine (Simon & Schuster, 2002). See also https://web.archive.org/web/20111102213104/http://www.bizofbaseball.com/docs/Brown_Collusion_Neyer_Blunders.pdf

The Washington Post indicated that the nine teams siding with Vincent were: the Montreal Expos, Houston Astros, New York Mets, Boston Red Sox, Baltimore Orioles, Texas Rangers, Oakland Athletics, and the expansion Florida Marlins, who had yet to play their first game. The abstention was Marge Schott, the Reds’ daffy, dog-toting, bigoted, Hitler-loving, impatient, impetuous, habitually chain-smoking owner whose raspy tones made Johnny Most sound like Johnny Mathis. According to the Post, Schott left the room before the vote was taken (I assume it was to go quaff yet another lung dart).

Also see Jon Pessah’s excellent book, The Game: Inside the Secret World of Major League Baseball's Power Brokers.

Sell, Dave. “Baseball’s Vincent Resigns.” Washington Post, September 8, 1992; https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/politics/1992/09/08/baseballs-vincent-resigns/4cdc5364-42ff-45d1-bacd-155d9f08e7e5/

Pessah, The Game, pp. 26-27 (Kindle e-book version).

“Selig Takes Office — ‘I Am a Fan.’” Associated Press, July 10, 1998.

MLB later moved the Office of the Commissioner to 1271 Avenue of the Americas in NYC.

Not every team has benefitted equally from TV. Those teams who also purchased an equity stake in their regional sports networks (RSNs) are faring much better. FanGraphs has a list that they update every year: https://blogs.fangraphs.com/lets-update-the-estimated-local-tv-revenue-for-mlb-teams/

A player needs 172 days (excluding postseason) on a big league roster to book one full year of MLB service time. A typical regular season, which begins around the end of March/early April, lasts around 183-185 days. That difference is what front offices exploit for service time manipulation.

Or “piece of metal,” as Manfred once less-than-eloquently put it.

Alternatively, I could be totally full of shit.