Be not afraid of greatness. Some are born great, some achieve greatness, and others have greatness thrust upon them.

--William Shakespeare, “Twelfth Night”

Greatness lies, not in being strong, but in the right using of strength; and strength is not used rightly when it serves only to carry a man above his fellows for his own solitary glory. He is the greatest whose strength carries up the most hearts by the attraction of his own.

-- Henry Ward Beecher, clergyman and abolitionist

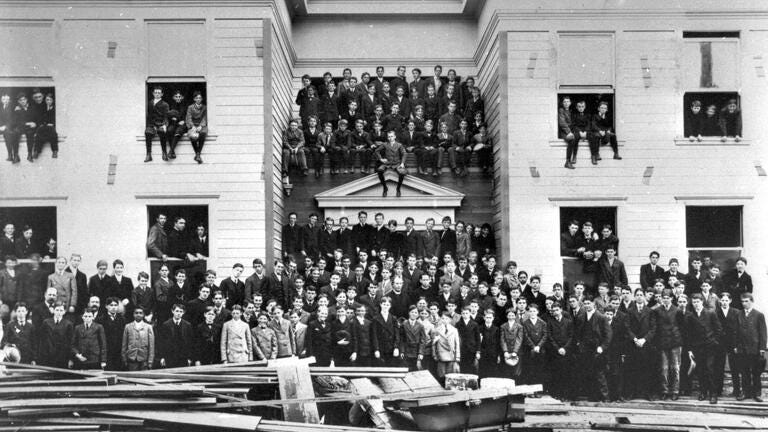

THE HISTORY OF DONS BASKETBALL stretches all the way back to 1910, when the school was known as St. Ignatius College and was housed in the hastily constructed “Shirt Factory” Church. Constructed after the 1906 earthquake and fire, the Shirt Factory was located at the corner of Hayes and Shrader Streets in what we today would refer to as the “NoPa” (North of Panhandle) district, an insipid appellation that was only recently forced upon us by the real estate tycoons who crusade around the city like an army of ants hoping to “rebrand” every inch in order to upsurge the land values. However, back in the Shirt Factory days, the area around Hayes and Shrader was an unpretentious settlement, comprised of sand dunes, nestled next to the northeast corner of Golden Gate Park.

Little is known about those early days of Hilltop hoops, other than the head coach was someone named Orno Taylor (that is, if Wikipedia is to be believed; a Google search for “Orno Taylor” resulted in nothing useful outside of some links to porn sites). The data on Sports-Reference.com goes as far back as the 1923-24 season, when St. Ignatius College, led by a coach named Jimmy Needles, went 14-4 while competing independently of a conference. Playing outside the auspices of a conference was quite common in those early days; other schools competing as indies in the Twenties included some familiar names of today: Arizona, Arizona State, Creighton, UCLA, St. Mary’s College of California, Santa Clara, Xavier, Duke, Rutgers, Villanova, Colgate, Butler, Davidson, Marquette, and Louisville. Lest you think there were no conferences, there were but a small handful compared to the present day. The Big Ten then, as now, had Michigan, Minnesota, Iowa, Ohio State, Illinois, Northwestern, Indiana, and Purdue. The Pacific Coast Conference, the forerunner to today’s Pac-12, claimed nine teams – Oregon, Oregon State, Washington, Washington State, Idaho, and Montana in the north, with Cal, Stanford, and USC in the south. Alabama, Kentucky, Mississippi State, Georgia, North Carolina, Florida, Virginia Tech, and Auburn, among others, resided in the Southern Conference, while the Southwest Conference boasted the likes of Texas, Texas A&M, Oklahoma State, Baylor, Arkansas, Rice, TCU, and SMU. If you’re wondering about schools such as Oklahoma, Nebraska, and Kansas, they were grouped into the Missouri Valley Conference along with Missouri, Iowa State, Grinnell (Iowa) College, and Drake.

In 1930, St. Ignatius College became the University of San Francisco and the basketball team responded with a rousing 12-6 record under Coach Needles. Illness forced Needles to resign in 1932, and on October 25, the Dons announced the hiring of recent graduate Wallace Cameron. A guard who was a gritty, tenacious defender, especially against larger forwards, Cameron had been the team captain during the 1929-1930 season, his senior year, and he was an All-Coast player twice during his stay at USF.

The USF Dons under Cameron were a mixed bag, going 10-7 and 8-5 in Wally’s first two years, plummeting to 7-14 in 1934-35, then rebounding to 11-9 the following year. In 1937, the Dons finally joined a conference, the short-lived Northern California Conference1, which consisted of four other teams: St. Mary’s, San Jose State, Santa Clara, and University of the Pacific. Conference play didn’t agree much with the Dons, as they went a combined 17-22 overall and 7-9 against fellow NCC squads over the two years that the conference existed. Back in the familiar environment of independent play in 1939, the Dons still scuffled, posting a mediocre 9-8 record, and falling all the way to 2-13 in 1940-41, a disastrous showing that cost Cameron his coaching job, though he stuck around campus as an economics professor. The 1941-42 Dons under Cameron’s successor, Forrest Twogood, finished a middling 14-10. Twogood might have been granted another year, but the U.S. was in the throes of World War II and the USF coach felt the pull of the military. In April 1942, Twogood left the Bay Area for the Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland, to begin training as an officer and, according to a blurb in the San Francisco Chronicle, to be “assigned to one of the four colleges training aviation cadets and will teach basketball, baseball, or football.”

To replace Forrest Twogood, USF both went back to the past and selected an in-house candidate. Jimmy Needles, who had resigned from the USF head coaching position ten years earlier, was hired to take over. In the intervening decade, Needles had become the head coach of the United States’ first Olympic basketball team, which competed in the 1936 Berlin summer games and won a gold medal, finishing ahead of Canada and Mexico. He also spent a short stint as the head coach at Loyola Marymount; two of his players there were men who would later make their marks on the Hilltop as coaches: Pete Newell and Phil Woolpert. Needles had returned to USF in 1941 to serve as the school’s director of athletics and would answer the call to retake the reins of the Dons basketball team after Twogood’s departure.

Needles would inherit a veteran roster in 1942, featuring the likes of Allen Wells, Al Dutil, Bill “Tiny” Bussenius, Bob “Red” Asselin, and “Mushy” Silver, the “Little Giant” who, despite his small stature, could pass and defend as well as anyone in college basketball. Nonetheless, the 1942-1943 team mustered a pedestrian 13-9 record, and they certainly weren’t helped by the in-season loss of Wells to a knee injury. After an 8-11 performance in 1943-44, World War II reared its head again; a sharp dip in enrollment and attendance at USF and campuses around the country due to the war made fielding complete rosters nearly impossible and forming schedules for a 1944-45 basketball season a non-starter. However, Japanese capitulation in August 1945, followed by the signing of their Instrument of Surrender aboard the USS Missouri in Tokyo Bay on September 2, ended the war.

Two days after the news of Japan’s surrender reached the U.S., USF announced that, basketball would return and that the new head coach would be Tiny Bussenius, USF star basketball player and boxer from earlier in the decade. The reunion between school and former player didn’t turn out as anyone had hoped; the 1945-1946 edition of the USF Dons went 9-12 and poor Tiny was punted off the Hilltop.

The Pete Newell Era

IT WAS A SHORT, FOUR YEAR period, but it was one that saw the Dons win their first championship and it was also a bridge of sorts between the era of treading quicksand, as the Dons had frequently done under Needles, Cameron, and Bussenius, and glory days to come under Phil Woolpert. Newell’s hiring was a fairly convenient one; having been released from Navy service at the end of World War II, Newell was already on campus as USF’s baseball coach. Pete’s first cager squad went an unimpressive 13-14 in 1946-47. The following year, the Dons improved to 13-11. Then, in 1948-49, came the best season in program history to date: a 25-5 record, finishing eighth in the final Associated Press rankings. The Dons’ attack was led by 6-foot-6 junior-transfer forward (and Oakland native) Don Lofgran, who averaged 14.7 points per game, and 6-foot-6 center Joe McNamee, who averaged 10.7 PPG. USF qualified for the prestigious National Invitation Tournament (NIT) – the first postseason tournament in program history – and took home the trophy, defeating Manhattan, Utah, Bowling Green, and a fellow Jesuit school, Loyola University of Chicago2, along the way. In the final, the Dons took a 27-19 lead into halftime, then allowed Loyola to tie the game at 47 apiece with under a minute remaining before a late free throw sealed the victory, giving the University of San Francisco its first national championship in basketball3. Lofgran, who had posted 20 points in the contest, was named the tournament’s Most Valuable Player.

The 1949-1950 team didn’t fare quite as well, but they still ended up 19-7 and 12th in the final AP voting and were invited to the 1950 NIT, where they fell in the first round to the eventual champion City College of New York, 65-46. Lofgran enjoyed another 15-PPG season and was selected in the first round of the NBA draft by the Syracuse Nationals (who would become the Philadelphia 76ers in 1963). McNamee was also drafted, in the first round to the Rochester Royals (now the Sacramento Kings), two spots before Lofgran.

One Don who wasn’t drafted, but made an impact nonetheless, was 5-foot-5 backup guard Willie “Woo Woo” Wong, who grew up in the city’s Chinatown district and honed his skills at the playground that now bears his name. A prep star first at Lowell High School, then at San Francisco Polytechnic, Wong once scored 40 points in a game and was named to the 1945 All-City team, the first Chinese-American play to receive the honor. He simultaneously starred for the San Francisco Saints, a traveling squad of Chinese-American players that played under the auspices of the American Athletic Union (AAU). Wong led the Saints to back-to-back Asian national tournament titles in 1948 and 1949. “He had good range,” Newell recalled years later. “Much farther than a smaller person like him should have had. Because he wasn’t as big as most players, he had to learn more about the game, too. He always seemed to make the right pass and never seemed to take a bad shot. And I'll tell you, he was a god in San Francisco’s Chinatown.”

Woo-Woo4 averaged 13 points per game on the freshman squad, then jumped to varsity in 1949, suiting up for the defending national champions. He played sparingly, making five field goals in 14 attempts, plus three-of-five from the charity stripe, for a total of 13 points for the season. But when the Dons took the court at Madison Square Garden on March 11, 1950, for the NIT, there was a large contingent of Asian fans in attendance to watch Wong, the first Chinese-American to play in the building’s history. Wong's name appears in the box score from that game, but he apparently attempted not a single shot.

Flush off his quick turnaround of the USF program, Pete Newell was suddenly being eyeballed by the larger programs. In May 1950, Newell resigned both his baseball and basketball coaching duties on the Hilltop and decamped for Michigan State University, where he would spend four fairly unremarkable years before returning to the Bay Area as the head basketball coach at the University of California.

From St. Ignatius to a Championship on the Hilltop

PHILIPP D. WOOLPERT WASN’T FROM San Francisco. Born in Kentucky and raised in Los Angeles, he played three seasons at Loyola University (now Loyola Marymount), graduating in 1940. He came to the San Francisco in 1946 to take over the basketball team at St. Ignatius High School, which up until 1927 had been a feeder school for the then-St. Ignatius College. In four years at SIHS, Woolpert went an incredible 63-29, a winning percentage of nearly 70 percent. So, when Pete Newell left the Hilltop for East Lansing, Woolpert seemed the natural choice. In fact, Phil had been trained in the Newell system and was highly recommended by the recently departed USF coach. On April 26, 1950, the union became official.

Phil Woolpert would take the program to the highest highs it had ever seen, ones that have not been reached since. And Woolpert, who grew up in an integrated neighborhood in L.A. with a politically liberal father, would become a racial trailblazer of sorts, whether he intended to or not.

William Felton Russell was born on February 12, 1934, in Monroe, Louisiana, a town that, like many Southern settlements of the time, was segregated and its Black residents frequent targets of racism. One day Russell’s father, Charles, had a shotgun stuck in his face by a white gas station attendant who insisted that the Black man wait until all the white customers were served first5. His mother, Katie, one day got an earful from a policeman for “dressing too fancy,” “like a white woman,” and threatening to throw her in jail.

The Russells packed up and moved to racially mixed Oakland, California, when Bill was eight. They weren’t the only Black family who fled upstate Louisiana and ended up in the East Bay Area’s biggest city. In 1945, a Baptist preacher named Walter Newton also moved his family, including his three-year-old son, Huey Percy Newton, from Monroe to Oakland, first settling in a house at 5th and Brush Streets, then to 18th and Castro. Russell’s family had taken up residence in the Acorn Projects, where, as Bill wrote in his 1966 autobiography, Go Up for Glory, “Pigs and sheep and chickens were raised in the backyard. A rotten, filthy hole. A firetrap with lights hanging off uncoated wires. It was the only place we could find.”6

Bill Russell took up basketball shortly after resettling in the Bay Area. However, despite his natural athleticism – he could run and jump well and had preternaturally large hands – young Bill struggled with the intricacies of the game and was cut from the Herbert Hoover Junior High School7 team. He tried again at McClymonds High School and barely made the roster, but the coach encouraged him to keep working on the fundamentals. The beneficiary of a massive adolescent growth spurt, the 6-foot-9 Russell became an extraordinary defender, albeit an unorthodox one. Whereas players were taught to defend flat-footed, Russell became a large leaper, jumping in the air to disrupt and block shots. He became a student of basketball, devoting time to studying and learning opponents’ tendencies.

Besides his Brobdingnagian size, Bill Russell had one other advantage.

He was left-handed.

Most shooters release the ball right-handed, which played into Russell’s sinistral strength. And they seldom, if ever, went against a left-handed defender. Over his time on the Hilltop, Russell became the most ferocious and fearsome shot-blocker in the country. “When you played Russell,” Pete Newell said, “nobody had really seen that shot-blocking technique. You were never ready for that hand coming out of the air. He made coaches look at big men in a different way.”8

Russell graduated from McClymonds in 1952, still a raw, uncoordinated prospect. No college recruiters showed any interest, except one. Hal DeJulio, an East Bay native who had played as a reserve on the Dons’ 1949 championship team and was somewhat of an “unofficial recruiter” for USF, was repulsed by the large kid’s lack of scoring and his “atrocious fundamentals,” but had astutely singled out one positive trait: Russell’s instincts, especially in big, important moments. Russell eagerly accepted a scholarship offer.

After spending one year on USF’s freshman team, under the guidance of Woolpert’s top assistant, Ross Giudice, Russell joined the varsity squad as a sophomore. Woolpert immediately handed Bill duties as the Dons’ starting center, and though he lacked bulk for someone his height – he looked like a toothpick on stilts – Russell made up for it with speed and the instincts that DeJulio had identified. Instead of focusing solely on the opposing centers, Russell would often attack the other teams’ forwards and contest their shots, making their lives miserable. He was a perfect fit for Woolpert’s preferred style of play, which prioritized long, half-court possessions on offense coupled with playing a stout full-court defense, and Russell was intimidating on the defensive end. “If you come in to shoot a layup off me,” he would snarl, “you’d better bring your salt and pepper because you’ll be eating basketball.” Quite often, he would make good on his promise.

Kezar Pavilion, a modest, cast-in-place concrete gymnasium opened in 1924 at 755 Stanyan Street, on the southeast corner of Golden Gate Park, had long served as USF’s primary home court. It was about to become a dimly lit house of horrors for opposing teams.

The 1953-54 Dons went a modest 14-7 overall, but posted an 8-4 record within their new conference, the California Basketball Association (CBA)9, good for second place. The Dons closed out the season with a four-game winning streak, vanquishing conference foes St. Mary’s, Pacific, San Jose State, and Santa Clara in order, outscoring them by a combined 271-215. USF basketball had all the appearances of an ascendant program: two great defenders in Bill Russell – who had transformed into the team’s leading scorer – and K.C. Jones, who came to the Hilltop as an academic risk but would go on to graduate in 1956 with his class. The roster also boasted an intelligent bundle of energy in guard Hal Perry, as well as Jerry Mullen, a 6-foot-5 forward who equally adept at scoring and rebounding, plus Warren Baxter, a 5-foot-7 blunderbuss of a reserve guard who was a capable outside-scoring threat and an outstanding dribbler.

When the Dons began the 1954-55 campaign by demolishing Chico State 84-55 and Loyola Marymount (at the time still an independent) 54-45, there was little doubt that USF was positioning itself to be a college basketball powerhouse in the near future. The Dons stumbled the next day, running out of gas against a very good UCLA team that was ranked No. 13 going into the game. Playing back-to-back days is not easy; doing so can be made excruciatingly difficult when the second game is against a John Wooden team that would spend several weeks ranked in the Associated Press’s Top 10.

What then followed was the greatest run in college basketball up to that point.

The Dons proceeded to reel off 60 straight victories straddling three seasons. After the UCLA loss, USF won 26 in a row, closing out ’54-’55 with the program’s second national championship by winning the NCAA Tournament. They defeated Colorado 62-50 in the Final Four semis, then crushed La Salle University 77-63 in the final. Russell was named the tournament’s Most Outstanding Player, averaging 21 points and 20 rebounds per game. Mullen, Bill’s frontcourt running mate who had averaged 13.6 points and 7 rebounds per game for the season, was selected in the second round of the 1955 NBA draft by the New York Knicks.

In 1955-56, USF went undefeated, winning all 29 games played, while once again sweeping their way through the NCAA Tournament, capturing their second consecutive national title and third overall. Russell led the way again with 20.6 points and 21 rebounds per game, Jones averaged 10 and 5, and sophomore Mike Farmer, a 6-foot-7 forward from Richmond High School who replaced Mullen, averaged 8.4 and 7.8 and was named to the All-Coast team.

The Dons Visit “The Rock”

AFTER WINNING THEIR SECOND-STRAIGHT title in 1956, USF’s starting five of Russell, Jones, Perry, Farmer, and Carl Boldt made a goodwill trip to Alcatraz, an event conspicuously absent from the local newspaper reportage of the time. Boldt recalled to the Boston Globe in 2014 how the prisoners “looked at Russell and they were just in awe.” In those days, the Rock’s population included the likes of Al Capone, Whitey Bulger, Mickey Cohen, and, yes, Robert Stroud, the famous “Birdman of Alcatraz,” who was certifiably cuckoo and serving punishment for slaughtering a prison guard. Officer John Hernan, who attended night classes at USF and went to the Dons’ games, led the players down “Broadway,” the walkway between the prison’s “B” and “C” blocks. The group also visited Alcatraz’s kitchen, hospital, and recreation yard, and broke for lunch with Stroud and the others. “Everyone was startled to see them,” prisoner Robert Luke recalled in his 2011 memoir Entombed in Alcatraz, “but it was a nice change.” Change had come to Alcatraz in ’55 when warden Paul Madigan, a sports fan who had played college baseball in Minnesota, took charge, and loosened some of the restrictions in the famously tight-run facility. For one, the prisoners were granted access to radio. There were only two stations available, but one of them regularly broadcast local sporting events, including Giants baseball, 49ers football, and USF basketball. The Dons soon became popular among the inmates.

“They were rooting for them,” remembered officer George DeVincenzi, “and every now and then when they’d win, they’d scream and holler out at the end of the game.”

Said Bill Baker, an inmate, “They were really popular at the time. We knew them. I loved them, K.C. Jones, and Bill Russell. Oh, yeah. There were cheers.” Listening to sports was “[o]ne of our main distractions,” Baker added.

The visit was arranged at the behest of Father Richard Scannell, who taught at USF, was also the prison’s Catholic chaplain, and was close with the Irish-Catholic warden Madigan. According to officer Hernan, the Dons’ appearance was meant to boost the morale of Alcatraz’s Black population. “The priest said, ‘They’ve been having a little trouble over there, and if you guys go over, it would help out,’” Boldt recalled in 2014.

“They treated us like we were gods,” the forward continued. “I’m not kidding. Like rock stars. That was it.”

“I remember against SMU, you had 26 points in the Final Four,” one of the inmates said to Farmer. “You were a great player.”

Betting on games was also a popular pastime within the prison walls. “We always bet on USF,” Boldt remembers one of the inmates saying. The gambling occasionally got heated, often with fatal results. “Some lost their lives over that shit,” said Pat Mahoney, a correctional officer who also operated the boat that ferried the inmates to the Rock. “If you couldn’t pay up, you got shanked.”

There was one Don who, not surprisingly, was the most popular subject on the visit. “They looked at Bill Russell like he was God,” Boldt said. Added Farmer, “He was very popular.”

The remarkable season and the Alcatraz visit represented an end of a short but prosperous era of USF Dons basketball. Both Russell and Jones would graduate and be drafted into the NBA, with Bill going in the first round to the St. Louis Hawks10 and K.C. in the second round to the Boston Celtics. Russell’s stint as a Hawk lasted mere hours, as he was subsequently dealt to the Celtics in exchange for six-time All Star “Easy Ed” Macauley, who hailed from St. Louis, and hook-shot master Cliff Hagan, who was fresh off a two-year military hitch and had yet to play basketball professionally but was a two-time consensus first-team All American while at the University of Kentucky. Now reunited, the two former Dons would team up to deliver eight straight NBA titles for Boston from 1958-59 through 1965-6611.

Meanwhile, back in San Francisco, the Dons began the 1956-57 season by winning their first five games, extending the streak to 60, before winding up on the sick end of 62-33 contest against the University of Illinois at Huff Hall in Champagne. Although the Dons would finish 21-7 overall and 12-2 against the newly rechristened West Coast Athletic League, which was good enough for conference’s the top spot, they weren’t really dominant anymore. Center Art Day was a competent scorer, but he was obviously no Bill Russell. Gene Brown, a junior guard, led the team with a 15.1 scoring average. Farmer, also a junior, enjoyed his finest season as a Don, averaging 12 PPG on 37.5 percent shooting, while also pulling down an average of nearly 10 boards per game. USF opened the season ranked No. 2 in the AP voting, behind Kansas, then slipped all the way to No. 19 after consecutive defeats by Illinois (the streak-breaking loss) and Western Kentucky and a narrow three-point victory over Washington (Missouri) University, a mediocre independent. Despite winning 11 of their final 12 games, the Dons finished the season unranked, but still received an invite to the NCAA tourney, where they dispatched Idaho State (66-51) and their cross-Bay neighbor, the Pete Newell-led California Golden Bears (50-46) before falling in the semifinal to the same Kansas team that they began the season ranked behind. USF defeated Michigan State 67-60 to win the third-place consolation game.

Even though 1956-57 saw the end of their dominant winning streak and marked the beginning of Life After Bill and K.C., there were still reasons to believe in the Dons going into 1957-58. Mike Farmer would be returning as an experienced senior leader, while Gene Brown and Art Day would also be returning as seniors. They would be joined by an intriguing sophomore prospect, who had been a two-time California Mr. Basketball while playing across the street at St. Ignatius High School.

“This Kid is Really a Basketball Genius”

FRED LACOUR WAS A PREP HOOPS legend who led the St. Ignatius High Wildcats to a composite 81-12 record and a pair of Northern California Tournament of Champions titles12. In the 1955-56 season alone, he scored 39 points in a game against in-city rival Galileo High School, and then torched Stanford University’s freshman team for 41, much to the amazement of Howie Dallmar, who could do nothing but sit and watch helplessly as his team was browbeaten and buried by this skinny God-damned prepster. “I couldn’t believe my eyes,” Dallmar was quoted later. “Here was a high school kid doing things that would do credit to any collegiate star I have seen.”

“This kid is really a basketball genius. It’s just a pleasure to see him play,” said SI head coach Rene Herrerias, who was on Pete Newell’s 1949 championship team at USF13 and would later succeed Newell at Cal.

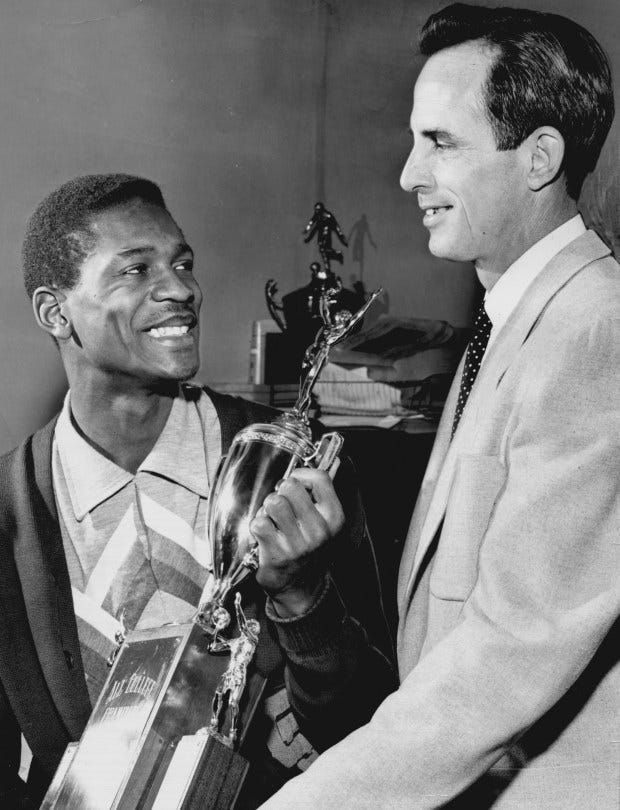

LaCour would complement the returning starters, tossing in an average of 12.4 points per game alongside Brown’s team-leading 14.2 PPG, Farmer’s 11.3, and Day’s 11.2, as the Dons went an undefeated 12-0 in WCAC play en route to a 25-2 overall record and a No. 4 ranking in the final AP poll. USF received their customary invite to the Big Dance, but were immediately upset, 69-67, by John Castellani’s Seattle University Redhawks, led by star forward Elgin Baylor, in front of a USF-friendly crowd at the Cow Palace. The Dons defeated Idaho State to win the regional third-place game, but it was only a small consolation.

The roster scattered after that season. Mike Farmer, Gene Brown, and Art Day all graduated. Farmer and Brown jumped to the NBA after being drafted by New York Knicks and the Boston Celtics, respectively. The 1958-59 Dons, playing in their freshly opened on-campus home, gave their supporters little to cheer about, going 6-20 overall and 3-9 in WCAC play. The irony lay thick: War Memorial Gymnasium, with its capacity exceeding 5,000, was an upgrade over tiny Kezar Pavilion, and it was paid for by a fundraising effort inspired by the back-to-back NCAA titles in 1955 and 1956. By 1958, the new building had come to fruition but without a championship-caliber team to fill the stands.

There was still one bright spot left in the form of LaCour, but there was little else, and even LaCour was having difficulties of his own. A man of mixed French Creole and African American heritage, Fred LaCour struggled with his racial identity while at USF and struggled to fit in. He began drinking and smoking excessively, gambling in card games, and skipping classes. “His attempts to integrate into a white-type culture met rebuff after rebuff,” Phil Woolpert recalled years later. “And he would not, or could not, identify as a Black person. The poor guy couldn’t win.”

LaCour dropped out of school halfway through the basketball season, leaving with a team-leading 17 PPG average through 12 games14. The Dons proceeded to lose seven in a row before eking out a 63-59 victory at War Memorial over Loyola Marymount, then dropped both games of a Southern California road trip through LMU and Pepperdine. The season ended with the Dons splitting their final two home games, beating mediocre Pacific and then losing to a good Santa Clara team.

Woolpert Departs

IN ADDITION TO BRINGING TWO more championship banners to the Hilltop, Woolpert became a trailblazer in college basketball by featuring a trio African American starting players in Russell, Jones, and Perry. “Phil was so far ahead of other coaches in recruiting Black players it was scary,” Pete Newell said after Woolpert’s death in 1987. “There were a lot of rednecks back then.” Given the tenor of the times, the “rednecks” that Newell spoke of were never far away. “They’d throw money on the floor and holler out, ‘Monkeys,’” Mike Farmer recalled. “They’d throw bananas. They’d yell the ‘N’ word.” For Woolpert’s part, his reasoning was simple. “Phil’s philosophy was, ‘I’m going to play the best five guys,’” Farmer said. The coach also received his share of venom, including death threats as well as complaints from alumni. “I don’t care,” Phil once told the school president upon being presented with a list of grievances from alums. “They are the ones who are going to play.”

Said Bill Russell: “The most you can ask from a coach is a chance. Phil gave Black players a real chance.”15

Hal Perry believed that Woolpert “deserved as much respect as any coach, but even more than that, as much as any person in any phase of the civil rights movement […] He went through hell. Very few people knew it. As far as they knew, he was a coach and that was it.”16

The basketball team wasn’t the first USF athletics program to make a stand against racial injustice: just a few years earlier, in 1951, the football Dons, under head coach (and former Notre Dame star) Joe Kuharich, went 9-0 and were led by a pair of Black stars in Ollie Matson and Burl Toler. The Dons received an offered to play in the 1952 Orange Bowl, but only on the condition that Matson and Toler stay home. USF refused. “We pulled out of the bowl bid because it was the right thing to do, and the only thing to do – we were a family,”17 recalled Bob St. Clair, a white offensive lineman who would go on to play eleven years with the San Francisco 49ers, make five Pro Bowls, and receive election to the Pro Football Hall of Fame. The decision to forego the Orange Bowl prevented USF from realizing a significant financial windfall, and proved to be the death knell for the cash-strapped program. USF discontinued football after that season.

But basketball went on, and under Phil Woolpert’s guidance and the stellar play of his three Black stars, they captured the back-to-back national titles in 1955 and 1956. But by the time the Fifties were nearing its end, Russell, Jones, and Barry, along with other important players such as Farmer, were long gone. The sparkling new gym perched on the north side of the main campus was open, but the cupboard was bare. And with the successes came the pressure, and it eventually overwhelmed and consumed the coach. It also didn’t help that Woolpert had badly injured his back during a hiking trip in the Philippines. On the advice of his personal physician, Dr. James Daley, Woolpert asked for, and received, permission for a one-year leave of absence just days before the 1959 season was to commence. “My relations with the USF administration have been ideal,” he said, “[b]ut coaching is a nerve-wracking business, and although 90 per cent of my tension may be self-imposed, I have found it increasingly difficult. I feel I owe it to myself and my family not to continue in this fashion.”

The reins were kept in-house. At just thirty-five years old, Ross Giudice18 was eight years younger than Woolpert, but he had served as Woolpert’s top assistant and USF’s freshman-team coach for the last eight years, and before that, had played on the Dons’ first national championship team in 1949. It was the dark-haired, baby-faced Giudice’s underhand free throw made in the final minute that propelled USF over Loyola-Chicago in that National Invitation Tournament final. As the Dons’ frosh coach, he endured only one losing season. But even more important, he was credited with turning a tall, gawky, ungraceful Bill Russell into a dominant post player and the program’s most important player. Wrote Murray R. Nelson in Bill Russell: A Biography:

Bill credits Giudice with the real refinement and development of his game. Giudice offered to work individually with any player after practice almost any time, and Bill took advantage of that offer. He would often stay two or three hours after practice working with Giudice on his hook shot, his footwork, and his shooting technique […] Giudice worked on the finer points of the game that Bill had never really been schooled in – setting screens and getting through them, making different passes for different situations, and most importantly, perfecting the hook shot. […] Once Bill was able to perfect hooking with either hand, he became a constant offensive threat near the basket, something he had never been before.

“He was a marvelous teacher,” enthused Vince Boyle, a backup center on the 1955-56 team. “Those championships would never have happened without Ross.”

Ultimately, as good a teacher as Ross Giudice was, he could not overcome the lack of talent available to him. The 1959-60 USF Dons finished 9-16 overall, 5-7 in WCAC play. The roster was dotted with sophomores and transfers, guys like Charlie Range and Bob Ralls and Bob Gaillard and Fred Bruener, none of whom possessed the otherworldly skills that Russell and Jones did. Giudice stepped down after the season. He would never coach again.

The 1960s: A New Coach, A New Era

SAN FRANCISCO IN THE 1960s represented as a period of change and tumult that contrasted sharply with prior decades of staid conservatism. The Sixties were period of hippies and Hells Angels and mind-bending drugs; a period of music and free love and free expression; a segment of Baby Boomers born in the first few years after World War II had come of age and rebelled against the traditional mores espoused by their Silent Generation parents. The Sixties were a time to, as Dr. Timothy Leary expressed it, “tune in, turn on, drop out.” This was an epoch that also featured demonstrations against the Vietnam War, the rise of Black Power, and the height of the civil rights movement. It was a juncture that was compelling enough for the likes of Joan Didion and Hunter S. Thompson to compose extensive chronicles of what was happening within the 49 Square Miles. Early rumblings were apparent late in the previous decade, when North Beach habitués such as Allen Ginsburg and Jack Kerouac were penning tomes like Howl and Other Poems and On the Road, respectively – the ribald imagery19 in the former causing such a ruckus among the Establishment squares that the police were called in to ransack City Lights Bookstore on Columbus Avenue, arresting the store’s manager – but the city’s leftward shift exploded during the 1960s. The San Francisco Sixties ended with the Vietnam war still raging, and the hippie movement petering out, leaving the Haight-Ashbury a desolate, boarded-up haven for speed freaks. There was the unjustified shooting death in 1968 of Richard Bunch, a Presidio stockade prisoner. Finally, in 1969, an innocent cabdriver, Paul Stine, was murdered in cold blood by the Zodiac Killer, an intelligent but deranged psychopath who had already snatched lives in Benicia, Vallejo, and Napa. The killer subsequently bragged about his exploits in chicken-scratch communiqués sent to media and law enforcement, often featuring exhaustively crafted ciphers that would’ve given the Bletchley Park Codebreakers aneurysms. Five decades later, the Zodiac Killer’s identity is still unknown (whomever he was likely fled this mortal coil many years ago), making the killings one of the great unsolved mysteries of Twentieth-Century Americana.

In the safe and relatively isolated cocoon of Hilltop hoops, change was also afoot. With the 1950s and the era of Phil Woolpert, Bill Russell, and K.C. Jones firmly in the rear-view mirror, it was time to face the future and install some winning teams into War Memorial Gymnasium that would create the same buzz that had once been the zeitgeist of the small, dingy Kezar Pavilion. To lead this next era of Dons basketball into the next decade, USF turned to Peter Paul Peletta, who had attended classes and played basketball down the road at Santa Clara University before transferring to Sacramento State, graduating in 1950. His coaching career started humbly enough, as a twenty-one-year-old high school baseball and basketball coach in tiny Lincoln, California, a hamlet of about 2,400 residents located in Placer County and roughly thirty miles north of Sacramento. As the baseball coach, Peletta handled the groundskeeping duties and the laundry. On the hardwood Pete could be a bit of a hard-ass, to the point of even kicking his barber’s son off the team and forcing himself to drive seventeen miles just to get a damn haircut. After stints at a pair of Sacramento high schools, Peletta moved on to coach hoops at Monterey Peninsula College, a program that was in the deepest depths of the doldrums – they hadn’t won a league game in five years – and also didn’t pay worth a shit, so taking the job represented a salary cut for Peletta. During their time in Monterey, Peter and his wife, Ginny, often teetered on the brink of financial insolvency. Peletta nonetheless turned MPC around, going 48-25 over three seasons.

On a whim, Peletta applied for the USF vacancy, even if he felt he had less than a snowball’s prayer in hell of getting it. “I didn’t think I had a chance and wasn’t too concerned about it,” he admitted in 1966. “I kept reading the papers and never saw my name mentioned. They had everybody in there but the janitors.” But, hey, you live but once, right? And serving at a private Jesuit school with a Division I basketball program only a half-decade removed from championship glory certainly paid well and came with perks. To the surprise of many, on March 25, 1960, USF announced the thirty-two-year-old Pete Peletta’s hiring in a noontime press conference at Phelan Hall.

Naturally, it was met largely with silence and bemusement around the Hilltop and beyond. Who the hell is this guy, Pete Pilotta? Poletta? Palooka? He’s from Monterey Peninsula where? And he has a history of getting ulcers? Sorry, but the USF opening is not the career move for someone with a tender stomach. Little did anyone know, Pete’s persistent tummy troubles, egged on by a sumptuous diet of cigarettes and coffee and stress, would crop up later on.

Yet, the hiring made sense from a scheme standpoint, at least according to USF athletic director Reverend Joseph Keene, S.J. “We have had our eye on Pete for some time,” Father Keene said at the time, “even before he was interested. He employs the [ball control] system20 of successful USF coaches like Pete Newell, Phil Woolpert, and Ross Giudice, and he is a gentleman who will be an asset to the University.”

For his part, Peletta ran late for the press conference and received a speeding ticket en route.

Peletta’s first team, in 1960-61, was at least encouraging, as their 8-4 conference record was good enough for second place in the WCAC, finishing behind 10-2 Loyola Marymount, the sole team in the conference to receive an NCAA tourney berth. The 1961-62 team represented a stark regression, with losing records both overall and within the conference, and a sixth-place finish out of seven teams21. But they had a promising sophomore guard by the name of Jim Brovelli, who averaged 10.5 points per game and nicely complemented senior guard Bob Gaillard’s 17.6 PPG average.

It was in 1963 that everything began to click on the Hilltop for Pete Peletta. Buoyed by a 17.3-PPG, 14.3 rebound-per-game season from sophomore center Ollie Johnson, the Dons went 18-9 overall – including a pair of victories over a couple of independents (and future conference rivals) in Portland and Gonzaga – and 10-2 in the WCAC, a first-place finish that punched the Dons’ ticket back to the Big Dance. The return to the NCAA Tournament proved to be short-lived, as they dropped a close 65-61 decision to Oregon State but defeated UCLA in the regional third-place game. No, it wasn’t a successful ending by most standards, but the program was clearly on the way up.

Yet, they never quite got over the hump. The 1963-64 team, led by Johnson, Brovelli, Dave Lee, and a couple of promising sophomores in forward Joe Ellis and guard Russ Gumina, swept their way through conference play and lost only five games overall, including three in a row in December to independents Oklahoma City University, Loyola-New Orleans, and the University of Miami22. It all culminated in a second-round loss in the NCAA Tournament to the same UCLA squad that the Dons had beaten a year earlier in the consolation game. The 1964-65 campaign produced similar results: 13-1 in-conference bolstering a 24-5 overall record, Johnson, Ellis, and Gumina providing the bulk of the scoring and rebounds, followed by losing to UCLA 76-72 in the second round of the tourney, a game in which USF led by 8 points at the half.

Johnson graduated and the Boston Celtics drafted him in the first round, eleventh overall. It would be up to Erwin Mueller, a 6-foot-8 junior from nearby Livermore who had been playing the forward position, to replace the departed big man.

The 1964-65 season proved to be a disappointment despite the final record. The Dons began the year 6-0, spent the entire month of December ranked in the Associated Press Top 5, and were 10-1 in mid-January. But the Dons fell out of the Top 10 rankings in February, primarily because of a loss to a mediocre Tulsa squad. USF rebounded by winning seven in a row before dropping a 67-65 decision to Pacific, a heartbreaking finish for the Dons, who watched Pacific’s Bob Krulish23 rebound his own missed shot and slam-dunk the game-winning basket as the 3,000-seat Pacific Pavilion erupted. It was the Dons’ only conference loss of the season. Still, USF finished at the top of the WCAC, but the end result of this season was the same damn thing as the last: a second-round loss to UCLA, this time 101-93.

Peletta Retires, Vukicevich In, Vukicevich Out

THE 1965-66 EDITION OF THE Dons went 22-6, including 11-3 in the WCAC, good for a second place finish in the conference. A fine year, but not a fun year, at least for Peletta, who began experiencing a relapse of his ulcer woes. He certainly wasn’t helped by the odd behavior of the senior forward-turned-center Erwin Mueller, Ollie Johnson’s replacement, a 6-foot-8 string bean equipped with an affinity for consuming mass quantities of Pepsi. While the bubbly, sugary cola inexplicable failed to grant him the needed weight gain, dairy apparently succeeded. Mueller had taken to a diet of milk and a daily quart of ice cream to keep his weight up. Occasionally, he’d lapse back into the soda habit. Joe Ellis, a senior forward, related to Sports Illustrated how he would hear Mueller’s boisterous fits of eructation on campus, “and then we know he’s been hitting the Pepsi again.”

Mueller’s fluctuating avoirdupois led to some inconsistent play on his part, which got on Peletta’s nerves. Also not helping were the constant questions about USF’s title chances, which the coach would evade by dancing around them with a Nureyev-like deftness. Despite the strong record, the Dons were not ranked all year, possibly due to a weak strength of schedule. Losing back-to-back games against Pacific and Loyola Marymount in March certainly didn’t help, and while the Dons were not invited to the NCAA Tournament, they did receive an NIT bid, beating Penn State on March 12, 1966, and then losing to Army three days later.

And with that, the Pete Peletta era had drawn to a close, and while it was just six years, it was overall a successful six years: the Dons went 114-51 (.691 winning percentage) while winning the WCAC in three straight seasons, appearing in the NCAA tourney three times and the NIT once. But Pete’s persistent ulcers demanded that he step away from coaching, though he would remain with USF as the athletic director for the next several years, a less-strenuous job that did not require answering reporters’ questions or putting up with a belching soda-fiend center.

Into the void stepped Phil Vukicevich, who had been on Peletta’s staff as an assistant. A left-handed shooting guard, Vukicevich played under Phil Woolpert from 1949 through 1953, that in-between period between the Dons’ first and second NCAA championships, and in his senior season he led the team in scoring with a 12.3 points-per-game average. Phil’s coaching tenure on the Hilltop would mark the end of the 1960s, and came with mixed results. Vukicevich’s teams did not finish higher than third place in the WCAC, and the 1968-69 team cratered to a 7-18 (overall)/3-11 (WCAC) record. That team began the year dropping contests to Pac-8 schools Oregon State and Cal, and would endure losing streaks of three, seven, and three games. When the 1970-71 squad began the year 0-6, Vukicevich decided he’d had enough and pulled the ripcord, but it wasn’t only the slow start that factored into his decision. “I had been thinking about it before the season,” he was quoted in the San Francisco Chronicle. “When you find yourself in a position you can’t improve, I think a change might be best for the coach and the team.”

Another Former Star Takes The Reins

BY THIS TIME, THE UNIVERSITY of San Francisco men’s basketball program had established a pattern for hiring its former players to serve as coaches. The recently self-deposed Phil Vukicevich had played on the Hilltop in the late Forties and early Fifties. His predecessor, Pete Peletta, did not play for USF – he played at Santa Clara – and neither did Phil Woolpert and Pete Newell; but others, like Ross Giudice, Bill “Tiny” Bussenius, and Wallace Cameron, did. And now USF was about to replace Vukicevich with another former Don cager. And as the decade of the Seventies unfolded on the Hilltop with Bob Gaillard manning the controls, the problems that would culminate in the program’s self-imposed death penalty a decade later would begin to take root.

Next: “Part 2 - Probation” discusses the various infractions that led to the initial investigation in 1976 and culminated in the program’s first punishment three years later. To be alerted when posts go up, feel free to subscribe!

Sources:

Almond, Elliott. “‘So far ahead’: USF teams with Bill Russell, K.C. Jones made possible by forgotten coach,” San Jose Mercury News. September 8, 2020, https://www.mercurynews.com/2020/09/08/so-far-ahead-usf-teams-with-bill-russell-k-c-jones-made-possible-by-forgotten-coach/.

Bryant, Howard. Rickey: The Life and Legend of an American Original. Mariner Books, 2022.

Carmazzi, Rinaldo. “From the Pressbox” column, San Francisco Foghorn. February 5, 1943, pg. 3.

Chapin, Dwight. “Willie Wong -- 1940s Basketball Star,” San Francisco Chronicle. September 8, 2005, https://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/Willie-Wong-1940s-basketball-star-2610648.php

Connolly, Will. “Will Connolly Says…,” San Francisco Chronicle. July 25, 1941, pg. 3H.

“Don Lofgran (1969)” - https://usfdons.com/honors/hall-of-fame/don-lofgran/49/.

“Don Michael Farmer (1971)” - https://usfdons.com/honors/hall-of-fame/don-michael-farmer/39.

“ESPN Tells the Story of Football Team’s 1951 Stand Against Racism,” https://www.usfca.edu/news/espn-tells-the-story-of-football-teams-1951-stand-against-racism.

Faraudo, Jeff. “DeJulio, man who ‘discovered’ Bill Russell, dead at 83,” East Bay Times/Bay Area News Group. July 15, 2008. https://www.eastbaytimes.com/2008/07/15/dejulio-man-who-discovered-bill-russell-dead-at-83/

Friendlich, Dick. “Woolpert Quits USF ‘for Year’,” San Francisco Chronicle. November 28, 1959, pg. 1H.

Friendlich, Dick. “Peletta Is Named USF’s Cage Coach,” San Francisco Chronicle. March 26, 1960, pg. 27.

Friendlich, Dick. “USF Hoop Coach Vukicevich Quits,” San Francisco Chronicle. December 16, 1970, pp. 67, 72.

Green, Tom. “Woolpert, ex-USF Coach, Is School Bus Driver,” United Press International (archive). May 21, 1981. https://www.upi.com/Archives/1981/05/21/Woolpert-ex-USF-CoachIs-School-Bus-Driver/5729359265600/.

Holmes, Baxter. “Bill Russell, K.C. Jones Treated Like ‘Rock’ Stars at Alcatraz,” Boston Globe. October 11, 2014. https://www.bostonglobe.com/sports/2014/10/11/bill-russell-and-jones-treated-like-rock-stars-alcatraz/dYNqedPwyfFXNYHvGM84oN/story.html.

Horgan, John. “Fred LaCour: Gifted But Flawed Hoops Legend,” San Mateo Daily Journal. January 2, 2014, https://www.smdailyjournal.com/news/local/fred-lacour-gifted-but-flawed-hoops-legend/article_61d61746-1562-5b27-a190-0a8def48ac98.html.

“James Needles (1969)” - https://usfdons.com/honors/hall-of-fame/james-needles/86.

Jares, Joe “The Dons are Dreaming of Sweet Revenge,” Sports Illustrated/Vault.SI.com, February 14, 1966. https://vault.si.com/vault/1966/02/14/the-dons-are-dreaming-of-sweet-revenge.

Johnson, James W. The Dandy Dons: Bill Russell, K.C. Jones, Phil Woolpert, and One of College Basketball's Greatest and Most Innovative Teams. University of Nebraska Press, 2009.

“Kezar Floor Beating Opens Tomorrow Eve,” San Francisco Chronicle. December 10, 1942, pg. 3H

Nolte, Carl. “Ross Giudice, USF basketball Coach in Championship Era, Dies,” San Francisco Chronicle/SFGate.com. July 20, 2017. https://www.sfgate.com/bayarea/article/Ross-Guidice-USF-basketball-coach-in-11303174.php

“Pete Peletta Hinted New Don Coach,” San Francisco Chronicle. March 25, 1960, pg. 35

“Phil Woolpert Gets the Job,” San Francisco Chronicle. April 27, 1950, pg. 1H

“Philip Vukicevich (1977)” - https://usfdons.com/honors/hall-of-fame/philip-vukicevich/64

“Player Profile: Fred LaCour,” http://www.bigbluehistory.net/bb/NorthSouth/fred_lacour.html

SI Staff. “Scorecard,” Sports Illustrated/Vault.SI.com, December 6, 1965.

Taylor, John (2005). The Rivalry: Bill Russell, Wilt Chamberlain, and the Golden Age of Basketball. New York City: Random House. pp. 52–56.

Thompson, Tim. “Bill Russell Overcame Long Odds, Dominated Basketball,” The Current. University of Missouri–St. Louis, February 19, 2001.

“Twogood in Navy,” San Francisco Chronicle. April 11, 1942, pg. 1H

“USF Great Ross Giudice Passes Away.” https://usfdons.com/news/2017/7/20/dons-honor-club-usf-basketball-great-ross-giudice-passes-away.aspx

“USF Resumes Cage Sport,” San Francisco Chronicle. August 18, 1945, pg. 1H.

“USF Upset, Bruins Crush,” San Francisco Chronicle. February 27, 1965, pp. 33, 35.

“Wallace Cameron (1959)” - https://usfdons.com/honors/hall-of-fame/wallace-cameron/32

“Wally Cameron Will Coach Don Quintet,” San Francisco Chronicle. October 26, 1932, pg. 14H.

Not to be confused with the Northern California Athletic Conference (NCAC), which existed from 1925-1998 and consisted of football, baseball, men’s and women’s soccer, women’s volleyball, and women’s basketball.

Interestingly, Loyola University’s original name was also St. Ignatius College.

In the 1940s, the NIT was the preeminent postseason tournament in college basketball, and the teams that won it could officially claim a national title, as USF did in 1949. The NCAA Tournament, founded one year after the National Invitation Tournament, would eclipse the NIT in importance by the mid-1950s, thanks in large part to USF.

The nickname “Woo Woo” was bestowed by Bob Brachman, a San Francisco Examiner sportswriter, because that was what the crowd chanted every time Wong scored.

Thompson, Tim. “Bill Russell Overcame Long Odds, Dominated Basketball,” The Current. University of Missouri–St. Louis, February 19, 2001.

Quoted in Chapter 1 of Howard Bryant’s book on baseball star Rickey Henderson, Rickey: The Life and Legend of an American Original, in which he discusses other Black Bay Area sports legends and their backstories.

Hoover Junior High closed in 1974. It was located at 3263 West Street, in Oakland’s Hoover-Foster neighborhood and near the intersection of Interstate 580 and Highway 24. More here: https://localwiki.org/oakland/Herbert_Hoover_Junior_High_School.

Johnson, The Dandy Dons. Loc. 34 (e-book version).

The precursor to the current West Coast Conference. In 1956, the California Basketball Association was renamed the West Coast Athletic Conference, and in 1989 the “Athletic” was dropped.

Now the Atlanta Hawks.

Jones retired after the 1967 season but return to Boston in the Eighties to win two more championships as the Celtics’ head coach. Russell stayed with the Celts for two more seasons as a player-coach – Red Auerbach had retired in 1967 – and won two more titles.

This was in the era before the advent of sectional and state tournaments to determine high school basketball supremacy.

A 5-foot-9 guard, Herrerias averaged 5.3 points per game for the 1948-1949 USF squad. He graduated in 1950.

The St. Louis Hawks would draft LaCour in 1960 and given St. Louis’s nasty reputation towards Blacks and the Hawks’ internal practice of being rough on rookies, it was a mistake for LaCour to report. He left during the 1961-62 season, played for both San Francisco and Oakland teams in the short-lived American Basketball League, then resurfaced in the NBA with the San Francisco Warriors, their first season in the Bay Area after relocating from Philadelphia. Drug use, bad checks, and a failed marriage sent him further spiraling. Fred LaCour died on August 5, 1972, from cancer. He was just thirty-four years old.

Johnson, The Dandy Dons. Loc. 63 (e-book).

Johnson, The Dandy Dons. Loc. 58 (e-book).

“ESPN Tells the Story of Football Team’s 1951 Stand Against Racism,” https://www.usfca.edu/news/espn-tells-the-story-of-football-teams-1951-stand-against-racism.

After being hired, Giudice received a call from the NBC newsroom, which had just gotten word, asking for the pronunciation of the new coach’s surname. “Joodissey,” he replied.

Memorable lines, such as “yacketayakking screaming vomiting whispering facts and memories and anecdotes and eyeball kicks and shocks of hospitals and jails and wars” and “who sweetened the snatches of a million girls trembling in the sunset” and “who let themselves be fucked in the ass by saintly motorcyclists.”

Emphasis and clarification added.

Only San Jose State, which went 0-12 in the WCAC, was worse. The Spartans would leave the WCAC for the Pacific Coast Athletic Association at the end of the decade; the PCAA became the current Big West Conference in 1988.

Admit it: you’ve heard of only one of those schools.

The San Francisco Warriors drafted Krulish in the eighth round of the 1967 draft, but he never suited up.